Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > J Pathol Transl Med > Forthcoming articles > Article

-

Review Article

Breast schwannoma: review of entity and differential diagnosis -

Sandra Ixchel Sanchez

, Ashley Cimino-Mathews,

, Ashley Cimino-Mathews,

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4132/jptm.2025.08.12

Published online: November 3, 2025

Department of Pathology, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and The Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, MD, USA

- Corresponding Author: Ashley Cimino-Mathews, MD, Departments of Pathology and Oncology, The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, 401 N. Broadway, Room 2242, Baltimore, MD 21231, USA Tel: +1-410-614-6753, Fax: +1-410-614-9663, E-mail: acimino1@jhmi.edu

© The Korean Society of Pathologists/The Korean Society for Cytopathology

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- 49 Views

- 3 Download

Abstract

- Schwannomas are benign peripheral nerve sheath tumors composed of Schwann cells, which uncommonly involve the breast. Most breast schwannomas are clinically present as a superficial palpable breast mass but may also be detected on screening mammography. Excision is the preferred treatment if symptomatic, and these are not known to recur. Histomorphology is similar to other anatomic sites: bland spindle cells with wavy nuclei, nuclear palisading (Verocay bodies), variably hypercellular (Antoni A) and hypocellular (Antoni B) areas, myxoid stroma, hyalinized vessels and variable cystic degeneration. Classic immunohistochemistry is diffuse and strong labeling for S100 and Sox10. Notable diagnostic pitfalls specific to the breast include myofibroblastoma, particularly the palisaded variant, and fascicular pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia.

- Schwannomas are a well-described entity in soft tissue. These are benign peripheral nerve sheath tumors, composed of Schwann cells, most commonly occur in the head, trunk, and flexor surfaces of upper and lower extremities. Less described due to their rare nature are schwannomas that occur in breast parenchyma (2.6%) or axilla (5%) [1,2]. Although they resemble those of other anatomic sites, they pose a diagnostic pitfall with other spindle cell tumors in the breast [3]. The accurate diagnosis of this neoplasm, especially on small core biopsy specimens, plays a critical role for appropriate patient management and therapeutic options.

INTRODUCTION

- Schwannomas most often occur in adults in the third to fifth decade of life, with equal occurrences in males and females [1]. The pathogenesis of schwannomas is not well understood, although there are several hypotheses. One hypothesis is a genetic mutation or sporadic change leads to loss of merlin, which then causes overexpression of growth factors. This leads to tumorigenesis with decreased cell cycle arrest [4]. Another hypothesis involves genetic mutation(s) causing peripheral nerves to be vulnerable to stress and injury, which leads to unregulated Schwann cell proliferation and tumorigenesis [5].

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS

- Most schwannomas in the breast and other anatomic sites occur sporadically (90%). The remainder of schwannomas are attributed to various genetic alterations, and multiple occurrences may also be syndromic. A well described syndrome is Carney’s complex, which harbors PRKAR1a mutations [6], psammomatous melanotic schwannomas predominantly in the upper gastrointestinal tract and sympathetic chain, myxomas and Sertoli cell tumors [4]. Neurofibromin 2 (NF2)–related schwannomatosis due to alterations in NF2 [7] presents with numerous peripheral nerve sheath tumors, unilateral vestibular schwannoma, and meningioma [6]. Other types of schwannomatosis are due to loss of heterozygosity of chromosome 22q [7], and missense and truncating mutations of DGCR8 [6], LZTR1 [6], and SMARCB1 [6].

MOLECULAR FINDINGS

- Majority of breast schwannomas present as a palpable, mobile, and nontender mass [8], although pain has been reported in some cases [9]. Breast schwannomas may also be incidentally detected on screening mammography. Using the Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS), a system for standardizing mammogram reporting, these are often reported as 4A [8]. This category is considered suspicious for malignancy and is followed by an ultrasound and core biopsy [10].

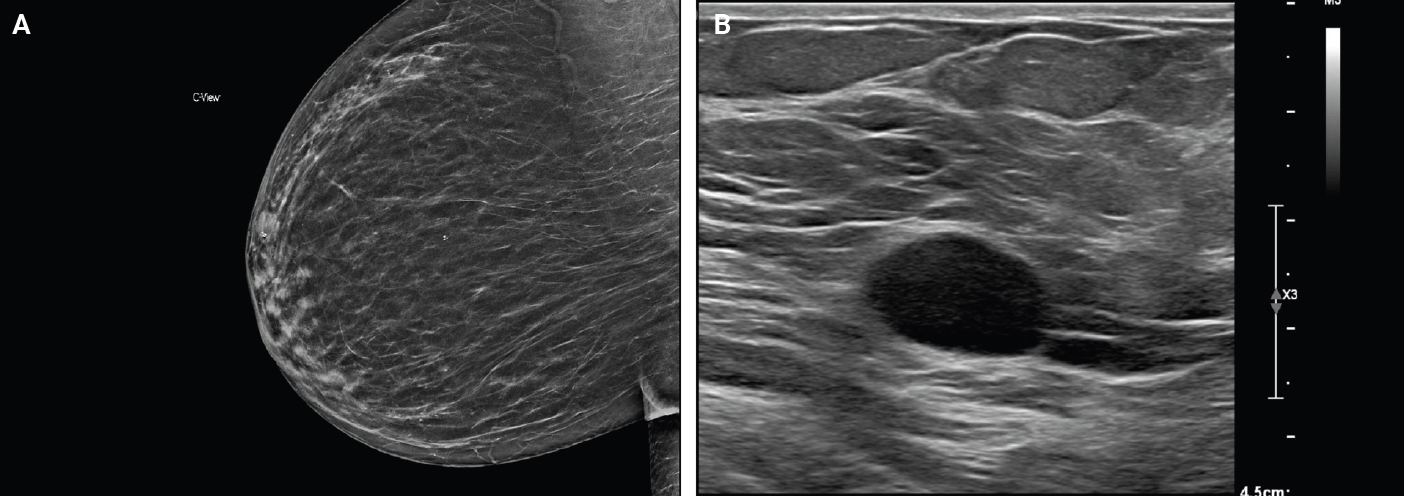

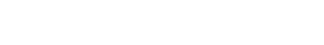

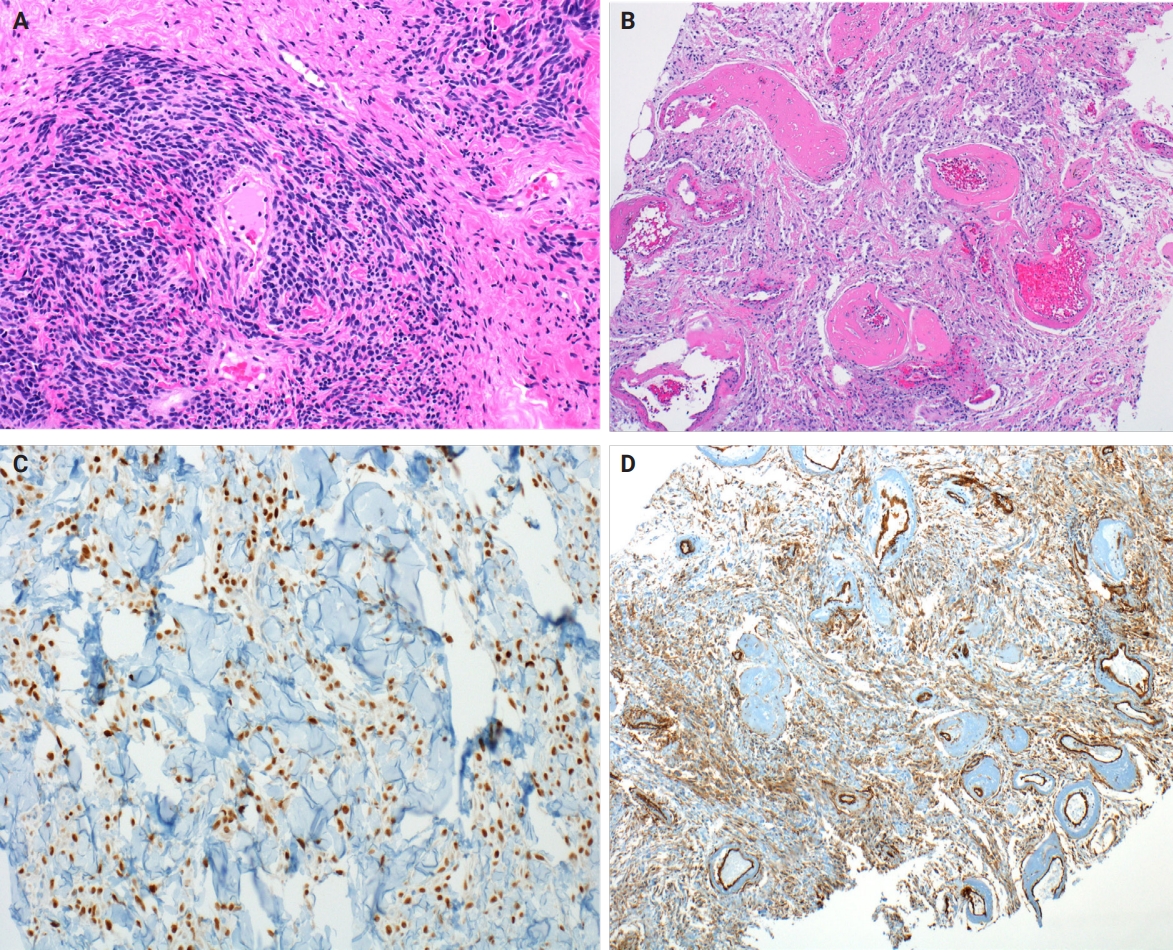

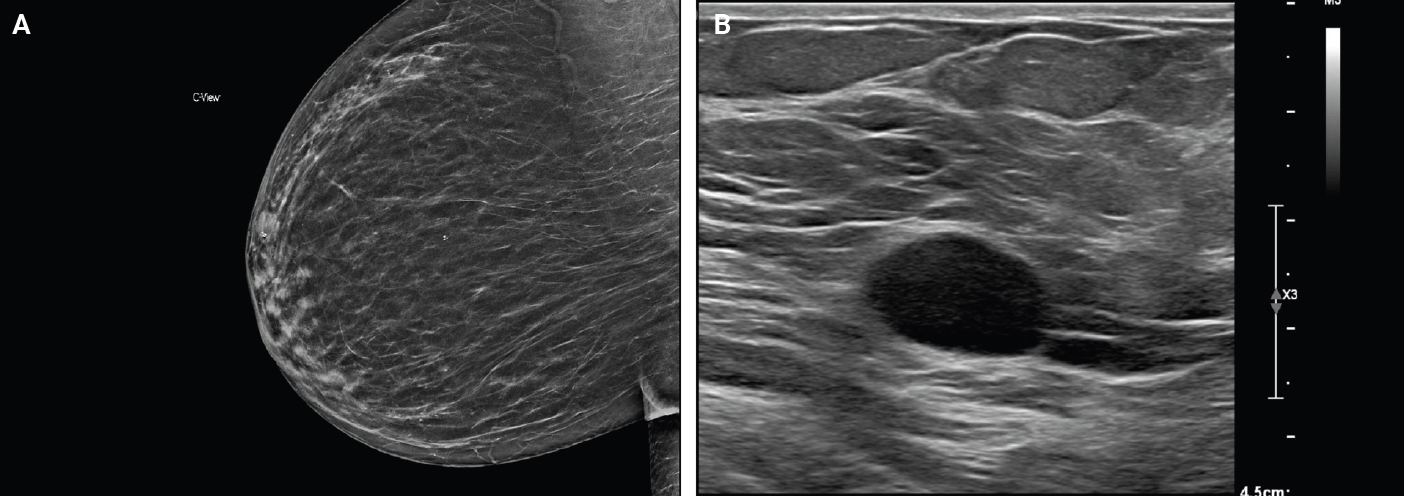

- On mammography, schwannomas present as a well-circumscribed, oval shaped, hyperdense nodule without microcalcifications (Fig. 1A). Ultrasound demonstrates a round/oval, well-circumscribed, homogenous, hypoechoic nodule with parallel orientation (Fig. 1B) [11,12]. Although not routinely performed, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is another modality to examine breast schwannomas. MRI T1 demonstrates a low signal and isointense nodule, while MRI T2 demonstrates a heterogeneous hyperintense signal with strong homogeneous contrast enhancement [13].

CLINICAL FEATURES AND RADIOLOGY FINDINGS

- Breast schwannomas are benign tumors with a favorable prognosis. Expectant management is appropriate if the lesion is stable and patient is asymptomatic. Surgical excision is recommended in cases where the lesion is growing or patient is symptomatic. There is no evidence of recurrence after excision [14].

PROGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

- Gross description

- Schwannomas have a similar gross appearance across anatomic locations, and none are unique to the breast. These often have a tan or yellow cut surface and are well demarcated from adjacent breast stroma. Degrees of hemorrhage and cystic changes are variable [4,15]. The plexiform variant of schwannoma has a distinct multinodular architecture [4].

- Frozen sections

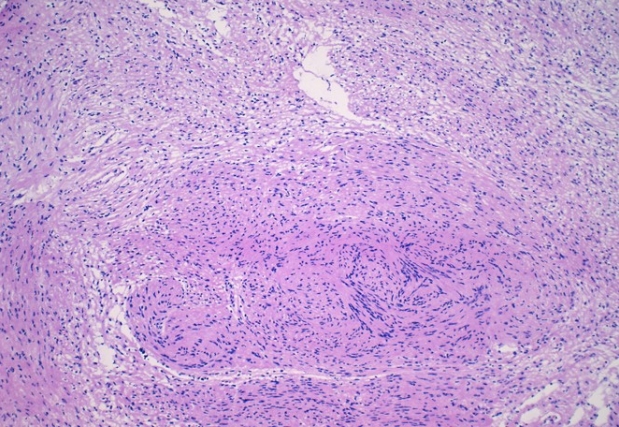

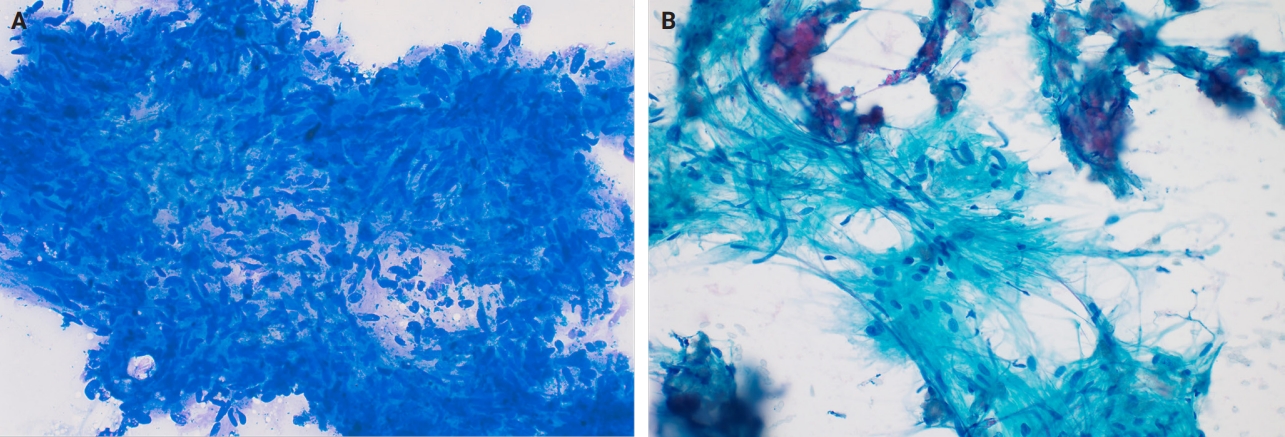

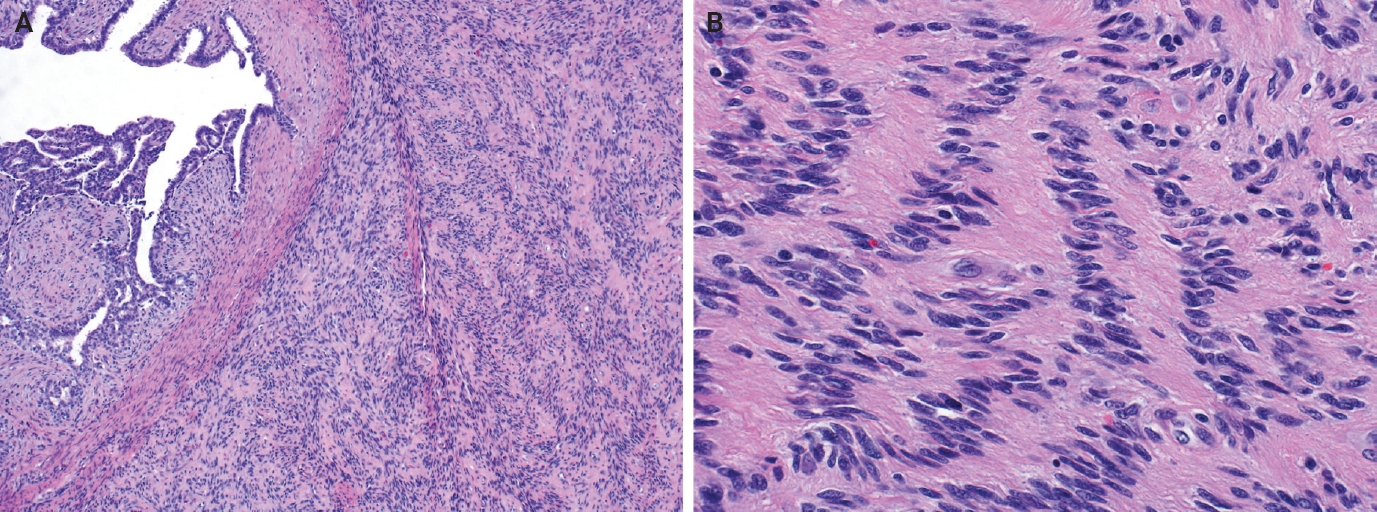

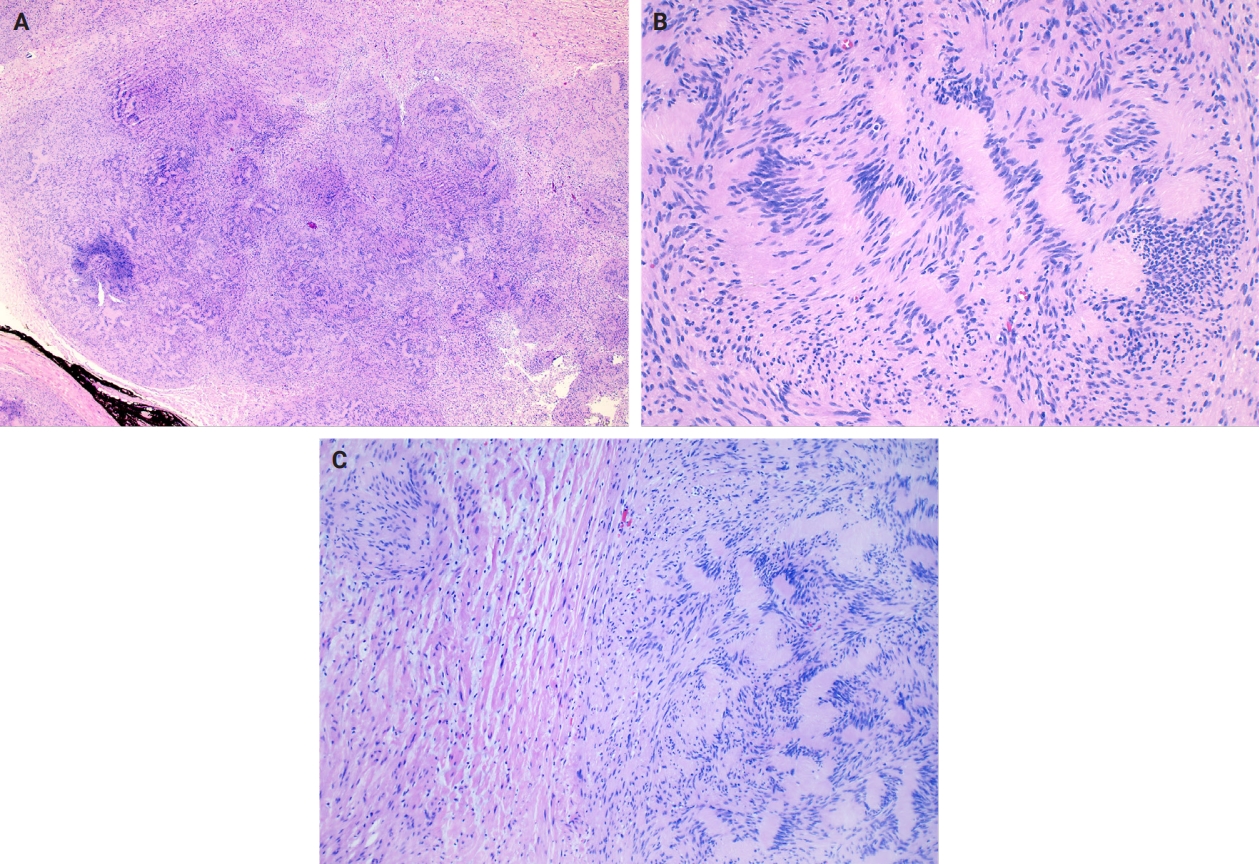

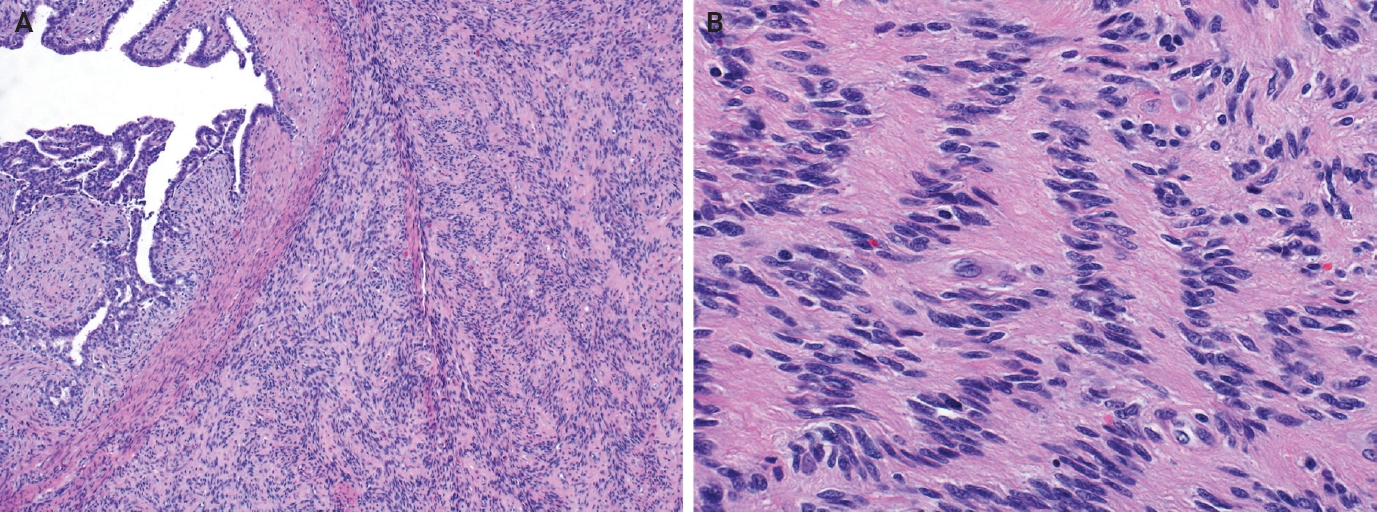

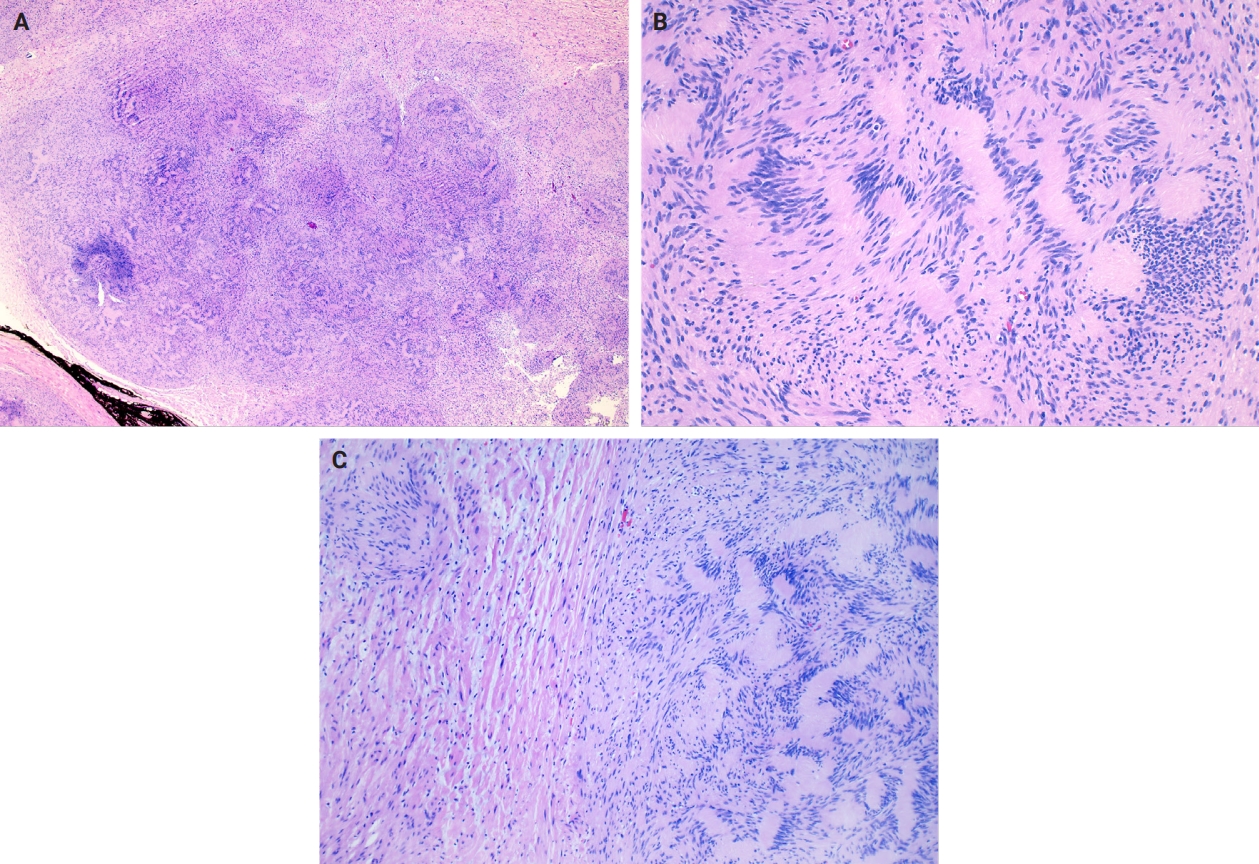

- Features on frozen section for schwannomas include a bland spindle cell proliferation with various degrees of cellularity (Fig. 2) [16,17]. Individual cells demonstrate anisonucleosis, and have wavy, elongated nuclei with tapering ends. These are arranged in parallel along the fibrillary and variably collagenous stroma. Hemosiderin deposition may also be present [17]. It is important to note that frozen artifact is often prominent, which includes cytoplasmic vacuolization and gaps between collagen. Nuclear freezing artifact may also lead to an incorrect impression of malignancy [18].

- Histomorphology

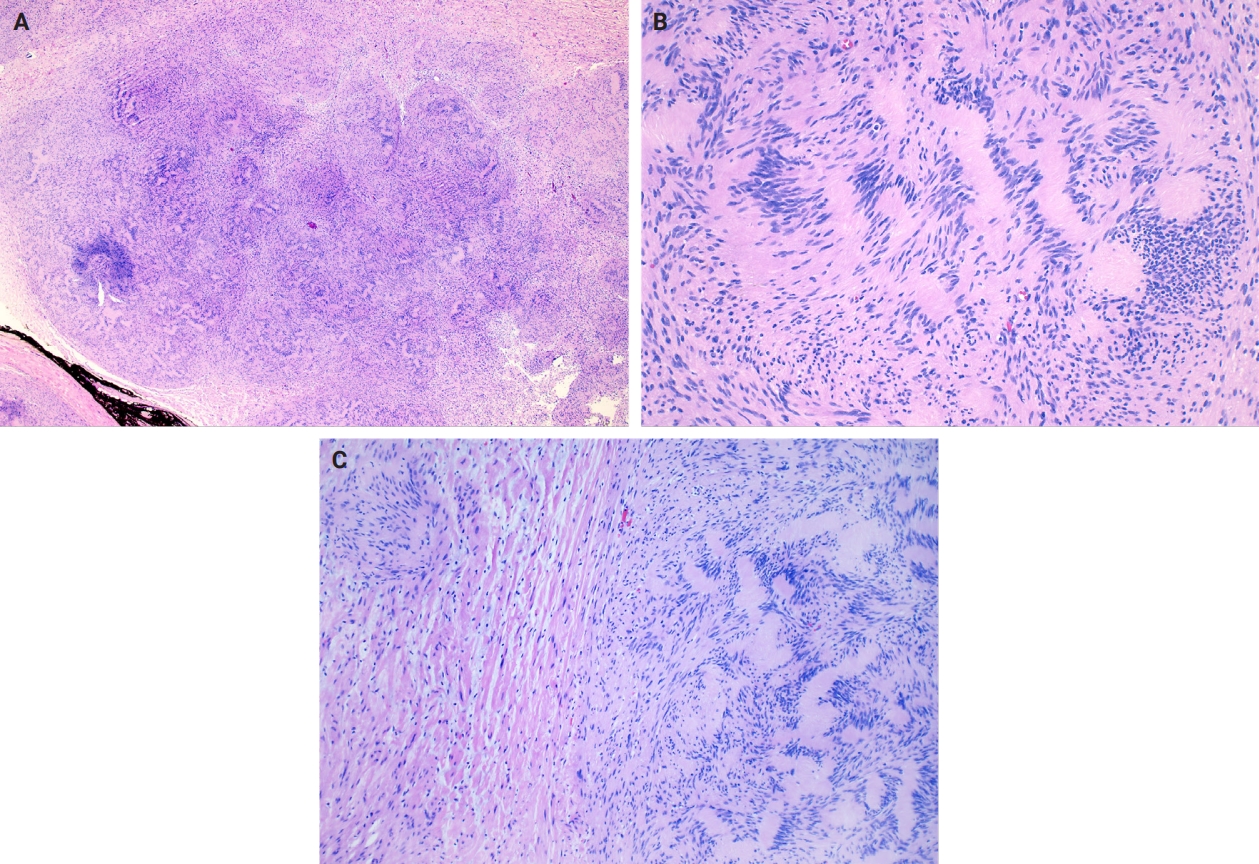

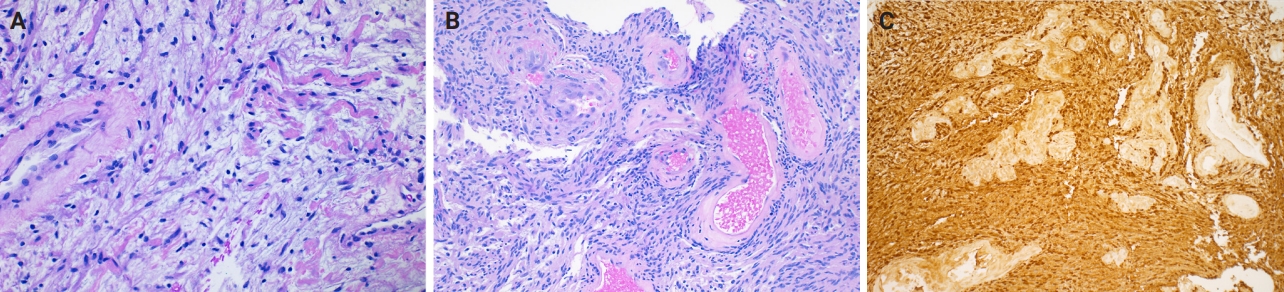

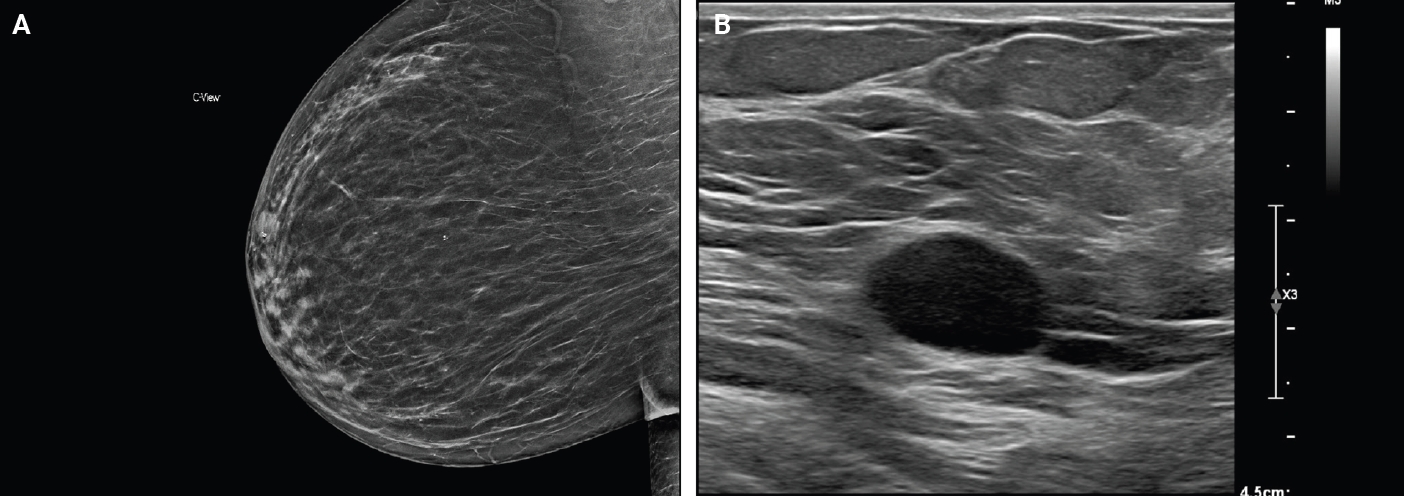

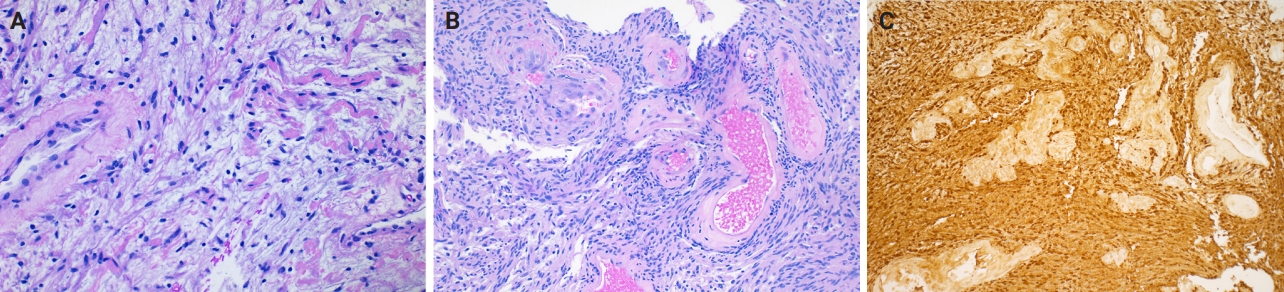

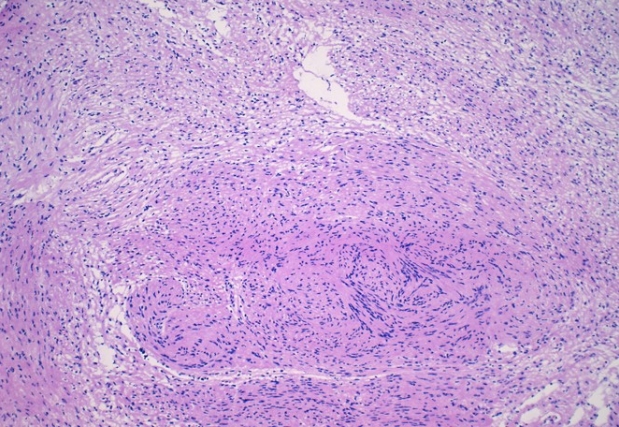

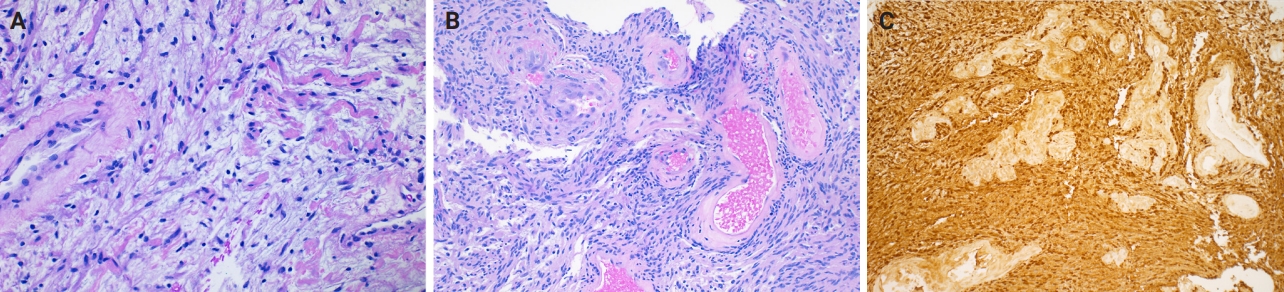

- Microscopically, breast schwannomas are well-circumscribed or encapsulated and can have prominent nodularity (Fig. 3A). Classic schwannomas have a bland spindle cell proliferation with various degrees of anisonucleosis, and wavy, elongated nuclei with tapering ends. These are arranged in parallel rows (nuclear palisading), also known as Verocay bodies (Fig. 3B). There is an abrupt transition between hypercellular (Antoni A) and hypocellular areas (Antoni B) (Fig. 3C). Antoni B areas have loose and myxoid stroma (Fig. 4A). Other key features to schwannomas include numerous small to medium sized vessels with prominent hyalinization and thrombi inside the lumen (Fig. 4B) and may also contain areas of hemorrhage or hemosiderin deposition [3,19].

- It is worthwhile to be aware of the schwannoma variants, which can cause diagnostic confusion due to the histologic variations. To briefly describe, ancient schwannomas often show degenerative atypia, calcifications, cystic degeneration and various degrees of hemorrhage [20]. Cellular schwannomas have areas with a predominant Antoni A pattern, fascicular growth, lymphoid aggregates, increased mitotic activity and infiltrate margins [20]. Plexiform schwannomas have intraneural-nodular pattern, rare mitosis, and are less well-circumscribed [20]. Epithelioid cell schwannomas are characterized with epithelioid cells displaying abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, nuclear pseudoinclusions and prominent nucleoli [19]. Reticular schwannoma is a rare variant that displays abundant myxoid change and microcysts [20]. The full profile of each variant is described in Table 1.

- Immunohistochemistry

- Immunohistochemistry is often needed to diagnose schwannomas, especially with small core tissue samples in the breast. The two most important positive stains are S100 (Fig. 4C) and SOX10, which are strong and diffuse in Schwann cells [3]. Schwannomas can also be positive for CD34 (weak, variable), calretinin, CD56, CD68 [21], podoplanin and Type IV collagen [22]. Classically, these are negative for estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2, smooth muscle markers (smooth muscle actin, desmin) and epithelial membrane antigen (capsule/perineurium only) [3]. Cytokeratins are generally negative, but may have rare labeling [23].

- Cytomorphology

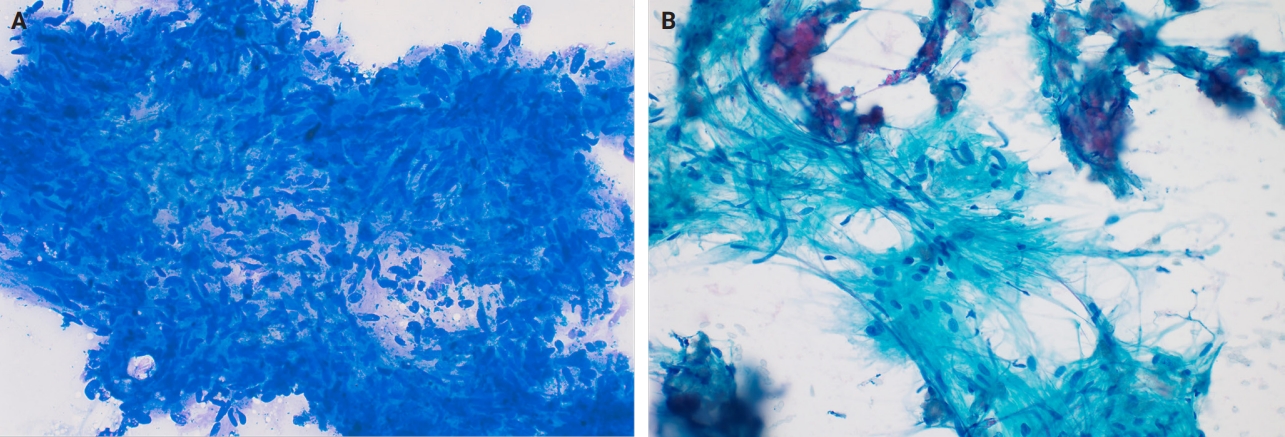

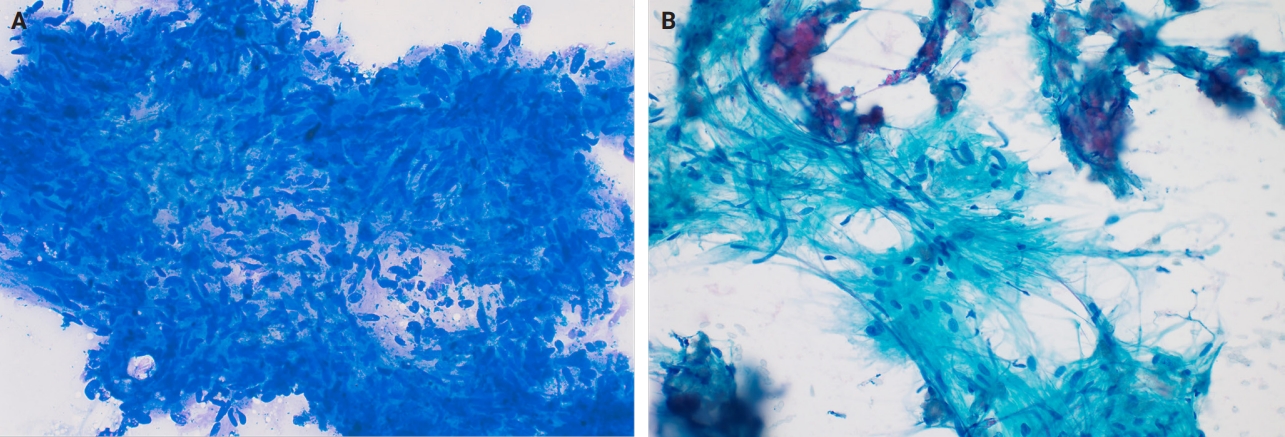

- Fine needle aspiration (FNA) of breast masses is performed worldwide, but less often in the United States, where core needle biopsy (CNB) is most utilized. Cytomorphologic features of schwannoma are similar to those of other anatomic sites. These include Antoni A areas with cohesive fascicles with variable cellularity, dense fibrillary matrix, and Verocay bodies. Antoni B areas have short spindle/wavy cells, myxoid background and microcysts (Fig. 5A, B). It is important to note the limitations for utilizing FNA to diagnose schwannomas. These specimens often have low diagnostic sensitivity (0%–40%), and are often unsatisfactory due to prominent cystic change, dense stroma, and hypocellular areas. CNB has now gained acceptance as a complementary method to FNA, which provides tissue for immunohistochemical studies [24].

- Differential diagnosis

- The differential for schwannomas is similar to other anatomic sites, including neurofibroma, neuroma, leiomyoma, nodular fasciitis, desmoid-type fibromatosis, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor, melanoma and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. However, it is important to note additional differential diagnoses particularly relevant in the breast.

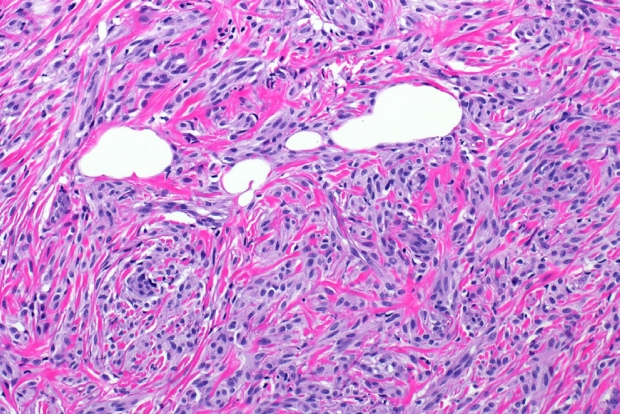

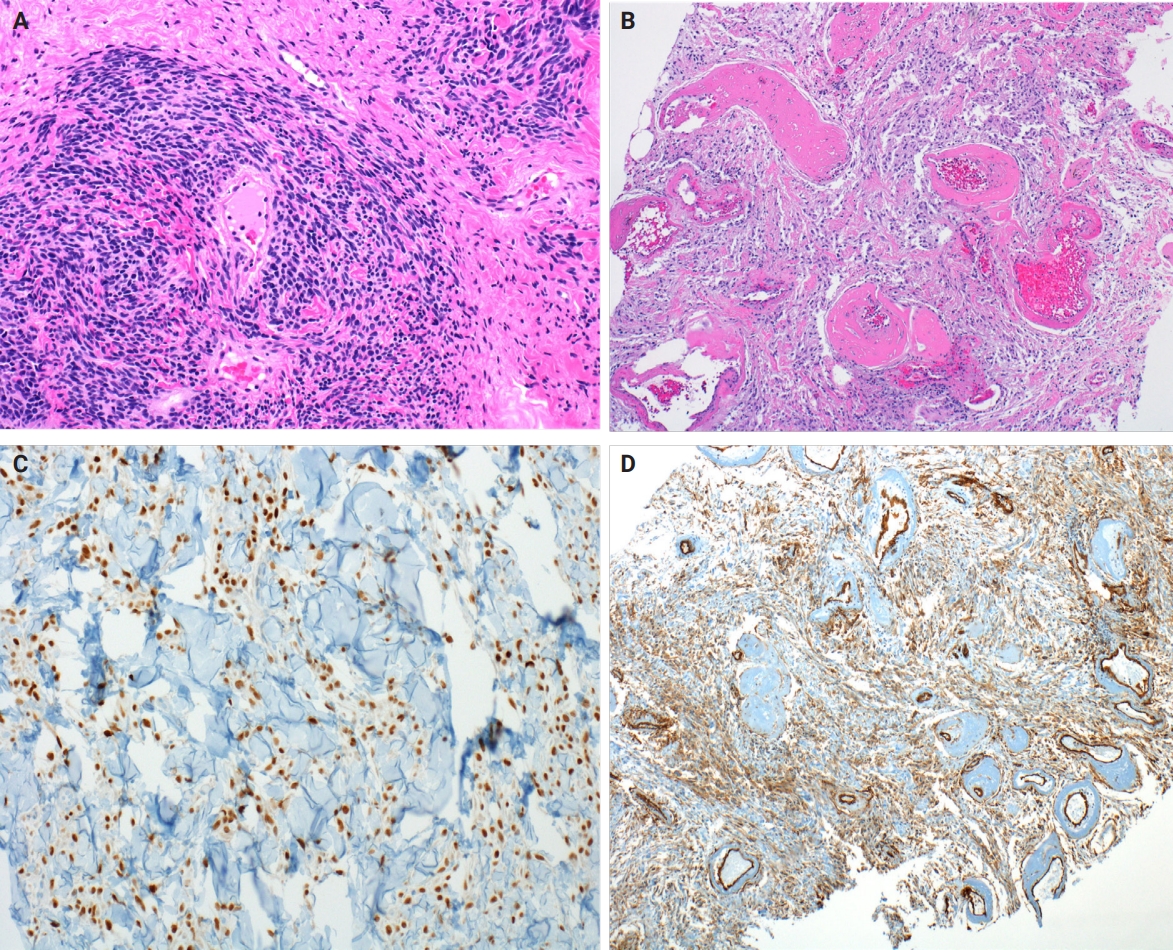

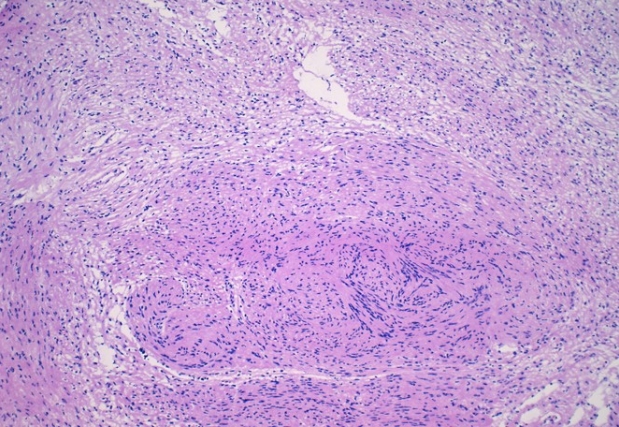

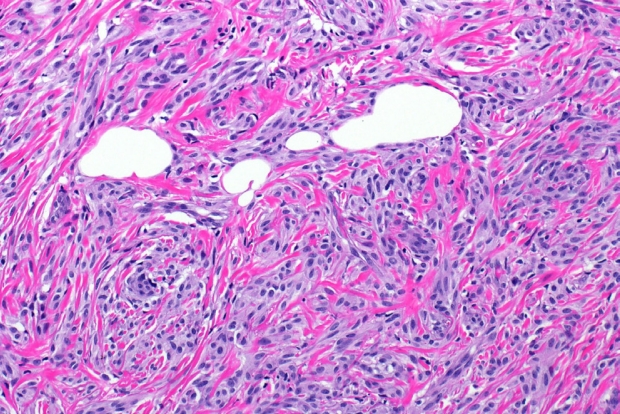

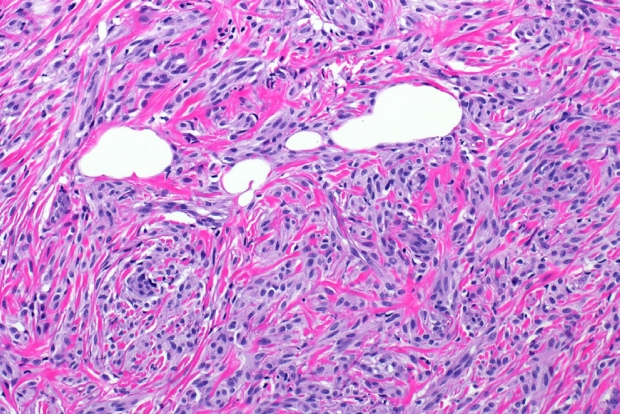

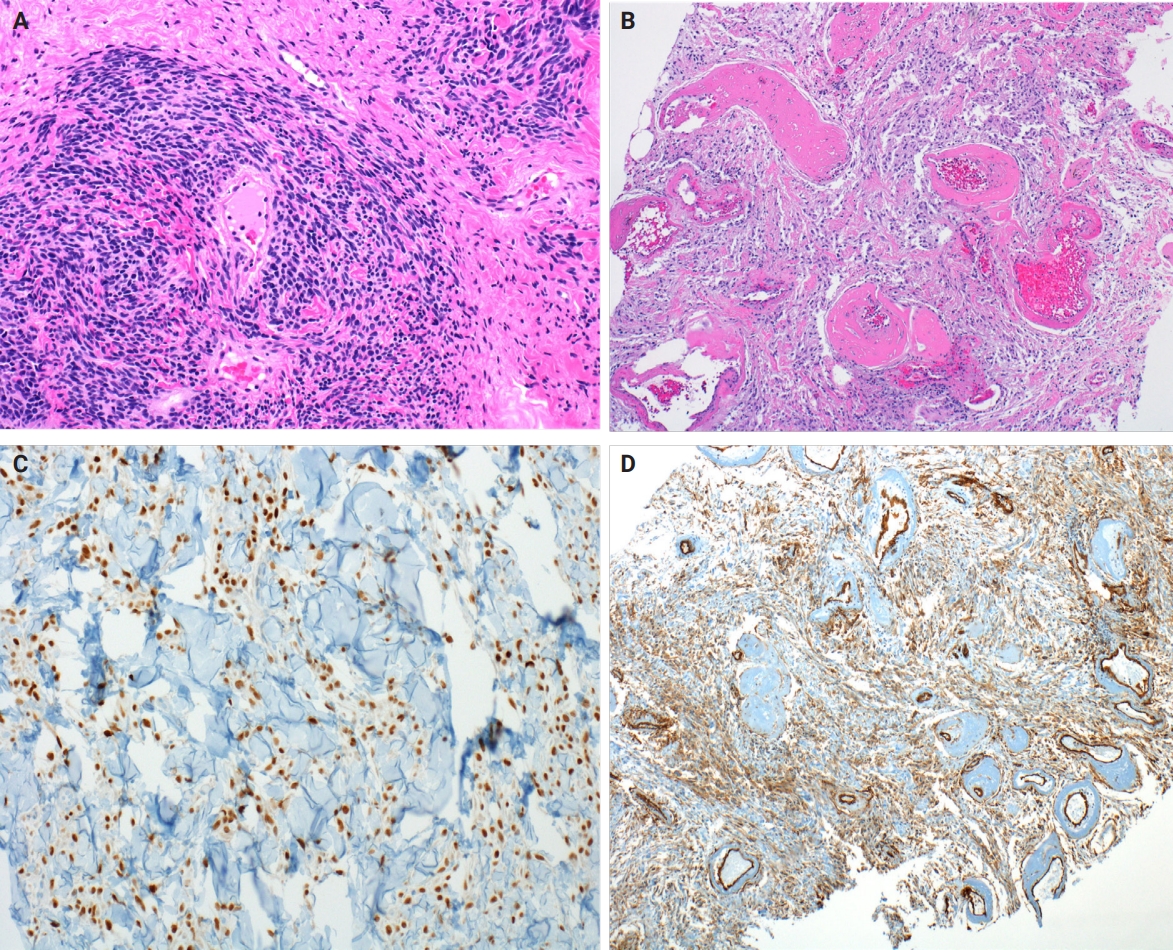

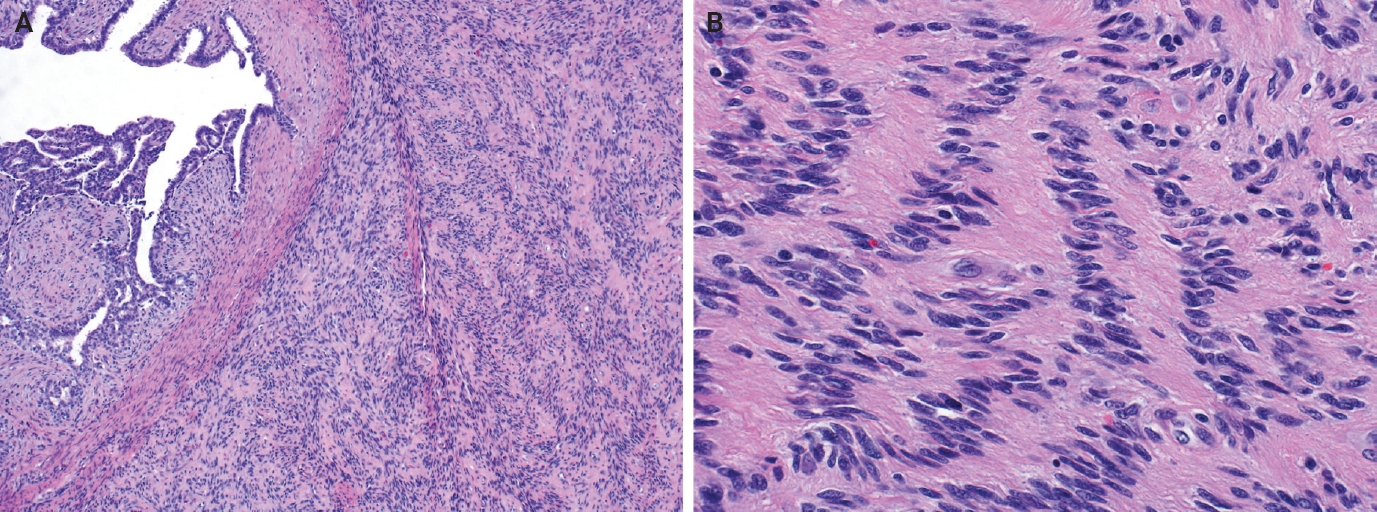

- Myofibroblastoma with classic features has bland spindle cells with amphophilic cytoplasm and bright eosinophilic collagen bundles and admixed adipocytes (Fig. 6). However, the palisaded variant has spindle cells with nuclear palisading and alternating cellularity, which resembles Verocay bodies and Antoni A and B regions, respectively (Fig. 7A). These may also contain gaping, hyalinized blood vessels (Fig. 7B), cystic degeneration, and myxoid stroma. On the contrary with schwannomas, myofibroblasts have strong nuclear immunoreactivity for ER (Fig. 7C) and membranous CD34 (Fig. 7D) [25,26]. Fibroepithelial neoplasms (fibroadenoma and phyllodes tumor) may contain stromal fascicular pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia (PASH)–like pattern with nuclear palisading (Fig. 8A). The lesional myofibroblasts may display elongated nuclei with palisading, resembling Verocay bodies of schwannoma (Fig. 8B) [3]. Fibromatosis-like metaplastic carcinoma is infiltrative, with fascicles of spindled cells displaying only mild to moderate cytologic atypia, including hyperchromasia and increased mitotic activity [3]. This entity is positive for a broad spectrum of cytokeratins, while schwannomas only have rare labeling [23]. PASH is hormone-dependent, which leads to an increase in stromal myofibroblasts which dissect through dense stroma. The myofibroblasts are spindled in morphology with tapering ends and occasionally wavy nuclei. Fascicular PASH has increased stromal cellularity with nuclear palisading, which overlaps in morphology with schwannoma [3]. A summary of key differentiating features of these entities is described in Table 2.

PATHOLOGIC FINDINGS

- Breast schwannomas have similar histologic features and immunophenotype as other anatomic sites. However, as with other breast spindle cell neoplasms, these can be particularly challenging on limited core biopsy material. Understanding histologic distinctions between the differential diagnoses and utilizing a selective immunohistochemical panel is key for classification of breast schwannomas.

CONCLUSION

Ethics Statement

Not applicable.

Availability of Data and Material

All data generated or analyzed during the study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files).

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation: SIS, ACM. Writing—review & editing: SIS, ACM. Approval of final manuscript: all authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no potential conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

No funding to declare.

- 1. Aref H, Abizeid GA. Axillary schwannoma, preoperative diagnosis on a tru-cut biopsy: case report and literature review. Int J Surg Case Rep 2018; 52: 49-53. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 2. Dialani V, Hines N, Wang Y, Slanetz P. Breast schwannoma. Case Rep Med 2011; 2011: 930841.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 3. White MJ, Cimino-Mathews A. Diagnostic approach to mesenchymal and spindle cell tumors of the breast. Adv Anat Pathol 2024; 31: 411-28. ArticlePubMed

- 4. Hilton DA, Hanemann CO. Schwannomas and their pathogenesis. Brain Pathol 2014; 24: 205-20. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 5. Helbing DL, Schulz A, Morrison H. Pathomechanisms in schwannoma development and progression. Oncogene 2020; 39: 5421-9. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 6. Dhamija R, Plotkin S, Gomes A, Babovic-Vuksanovic D. LZTR1- and SMARCB1-related schwannomatosis. In: Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, et al., eds. GeneReviews [Internet]. Seattle: University of Washington, 2024 [cited 2025 Mar 10]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK487394/.

- 7. Goetsch Weisman A, Weiss McQuaid S, Radtke HB, Stoll J, Brown B, Gomes A. Neurofibromatosis- and schwannomatosis-associated tumors: approaches to genetic testing and counseling considerations. Am J Med Genet A 2023; 191: 2467-81. ArticlePubMed

- 8. Parikh Y, Sharma KJ, Parikh SJ, Hall D. Intramammary schwannoma: a palpable breast mass. Radiol Case Rep 2016; 11: 129-33. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 9. Kang YJ, Woo OH, Kim A. Nipple schwannoma: a case report and literature review on nipple mass. J Breast Cancer 2024; 27: 72-7. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 10. Barazi H, Gunduru M. Mammography BI RADS grading. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island: StatPearls Publishing, 2023 [cited 2025 Mar 10]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539816/.

- 11. Uchida N, Yokoo H, Kuwano H. Schwannoma of the breast: report of a case. Surg Today 2005; 35: 238-42. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 12. Bellezza G, Lombardi T, Panzarola P, Sidoni A, Cavaliere A, Giansanti M. Schwannoma of the breast: a case report and review of the literature. Tumori 2007; 93: 308-11. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 13. Duehrkoop M, Frericks B, Ankel C, Boettcher C, Hartmann W, Pfitzner BM. Two case reports: breast schwannoma and a rare case of an axillary schwannoma imitating an axillary lymph node metastasis. Radiol Case Rep 2021; 16: 2154-7. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 14. Lee HS, Jung EJ, Kim JM, et al. Schwannoma of the breast presenting as a painful lump: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 2021; 100: e27903. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 15. Ashoor A, Lissidini G, Girardi A, Mirza M, Baig MS. Breast Shwannoma: time to explore alternative management strategy? Ann Diagn Pathol 2021; 54: 151773.ArticlePubMed

- 16. Kim C, Chung YG, Jung CK. Diagnostic conundrums of schwannomas: two cases highlighting morphological extremes and diagnostic challenges in biopsy specimens of soft tissue tumors. J Pathol Transl Med 2023; 57: 278-83. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 17. Fujita H, Tajiri T, Machida T, et al. Scoring system for intraoperative diagnosis of intracranial schwannoma by squash cytology. Cytopathology 2022; 33: 196-205. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 18. Tihan T. Schwannoma. In: Adesina A, Tihan T, Fuller C, Poussaint T, eds. Atlas of pediatric brain tumors. New York: Springer, 2010; 145-52.

- 19. Magro G, Broggi G, Angelico G, et al. Practical approach to histological diagnosis of peripheral nerve sheath tumors: an update. Diagnostics (Basel) 2022; 12: 1463.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 20. Rodriguez FJ, Folpe AL, Giannini C, Perry A. Pathology of peripheral nerve sheath tumors: diagnostic overview and update on selected diagnostic problems. Acta Neuropathol 2012; 123: 295-319. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 21. Park JY, Park H, Park NJ, Park JS, Sung HJ, Lee SS. Use of calretinin, CD56, and CD34 for differential diagnosis of schwannoma and neurofibroma. Korean J Pathol 2011; 45: 30-5. Article

- 22. Vijai R, Kumar JR, Arihanth R, Prabu M, Bharath N, Rahman K, et al. Schwannomas: atypical presentation and challenges. Case Rep Clin Med 2019; 8: 93-8. ArticlePDF

- 23. Fanburg-Smith JC, Majidi M, Miettinen M. Keratin expression in schwannoma; a study of 115 retroperitoneal and 22 peripheral schwannomas. Mod Pathol 2006; 19: 115-21. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 24. Ahn D, Lee GJ, Sohn JH, Jeong JY. Fine-needle aspiration cytology versus core-needle biopsy for the diagnosis of extracranial head and neck schwannoma. Head Neck 2018; 40: 2695-700. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 25. Laforga JB, Escandon J. Schwannoma-Like (Palisaded) myofibroblastoma: a challenging diagnosis on core biopsy. Breast J 2017; 23: 354-6. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 26. Magro G, Foschini MP, Eusebi V. Palisaded myofibroblastoma of the breast: a tumor closely mimicking schwannoma: report of 2 cases. Hum Pathol 2013; 44: 1941-6. ArticlePubMed

REFERENCES

Figure & Data

References

Citations

PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link-

Cite this Article

Cite this Article

- Cite this Article

-

- Close

- Download Citation

- Close

- Figure

Fig. 1.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 6.

Fig. 7.

Fig. 8.

| Schwannoma variant | Morphologic features |

|---|---|

| Ancient schwannoma | Degenerative atypia |

| Cystic degeneration | |

| Hemorrhage | |

| Calcifications | |

| Stromal hyalinization | |

| Frequent histiocytes and macrophages | |

| Cellular schwannoma | Predominantly Antoni A pattern |

| <10% of total tumor Antoni B area | |

| Fascicular growth pattern | |

| Foamy histiocyte aggregates | |

| Lymphoid aggregates | |

| Increased mitotic activity (usually <4–5 mitoses/10 HPFs) | |

| Coagulative necrosis (up to 10% of cases) | |

| Infiltrative margins | |

| Plexiform schwannoma | Intraneural-nodular pattern |

| Predominantly Antoni A pattern | |

| Absent to rare mitosis | |

| Less well-circumscribed | |

| Capsule may be absent | |

| Associated with NF2-related schwannomatosis | |

| Epithelioid cell schwannoma | Epithelioid cells: abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, nuclear pseudoinclusions, prominent nucleoli |

| Fibro-myxoid stroma | |

| Can have nuclear atypia | |

| Reticular schwannoma | Abundant myxoid change |

| Microcysts | |

| Rare variant | |

| Other rare features | Neuroblastoma-like schwannoma |

| Pseudoglandular structures | |

| Lipoblastic differentiation |

| Differential diagnosis | Histologic features | Immunohistochemistry |

|---|---|---|

| Myofibroblastoma, palisaded variant | Admixed adipocytes | Positive: CD34, ER; smooth muscle markers (SMA, desmin, calponin; variable) |

| Brightly eosinophilic, keloidal-like collagen bundles | Negative: S100, SOX10 | |

| Pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia (PASH) | Forms slit-like spaces mimicking vascular spaces | Positive: CD34, ER, PR, smooth muscle markers (SMA, desmin, calponin; variable) |

| Appears infiltrative due to involvement of intralobular and extralobular stroma | Negative: S100, SOX10 | |

| Fibroepithelial neoplasm (fibroadenoma and phyllodes tumor) | Benign epithelial component with intracanalicular, pericanalicular, or leaf-like architecture | Positive: CD34 (variable), smooth muscle markers (SMA, desmin, calponin; variable) |

| Infiltrative growth | Negative: S100, SOX10 | |

| Fibromatosis-like metaplastic carcinoma | Widely infiltrative | Positive: cytokeratins (AE1/AE3, 34betaE12, OSCAR; variable), p63 |

| Brightly eosinophilic keloidal-like collagen | Negative: S100, SOX10 | |

| Associated low-grade adenosquamous carcinoma |

HPF, high power field; NF2, neurofibromin 2.

ER, estrogen receptor; SMA, smooth muscle actin; PR, progesterone receptor.

E-submission

E-submission