Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > J Pathol Transl Med > Volume 59(6); 2025 > Article

-

Original Article

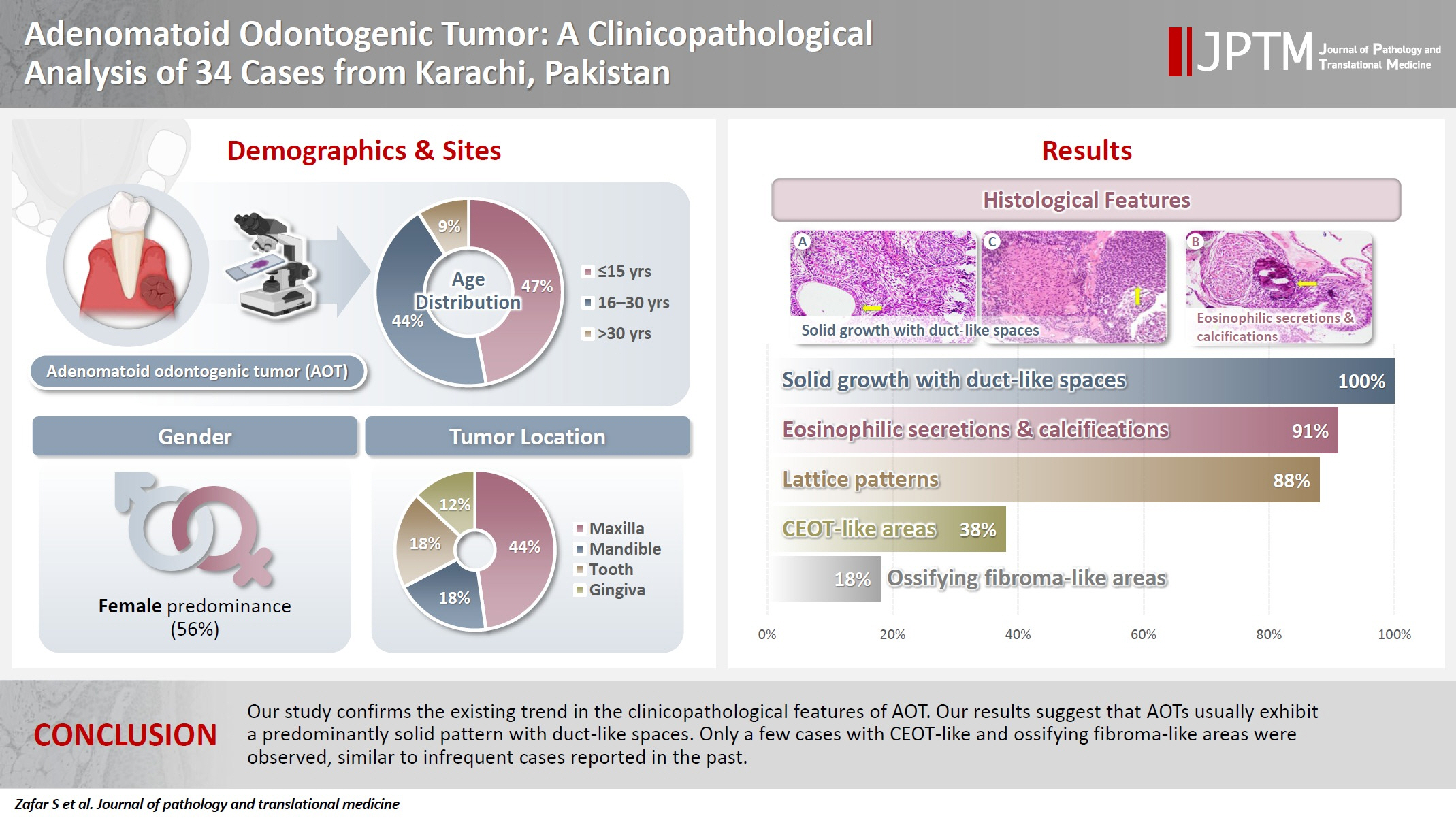

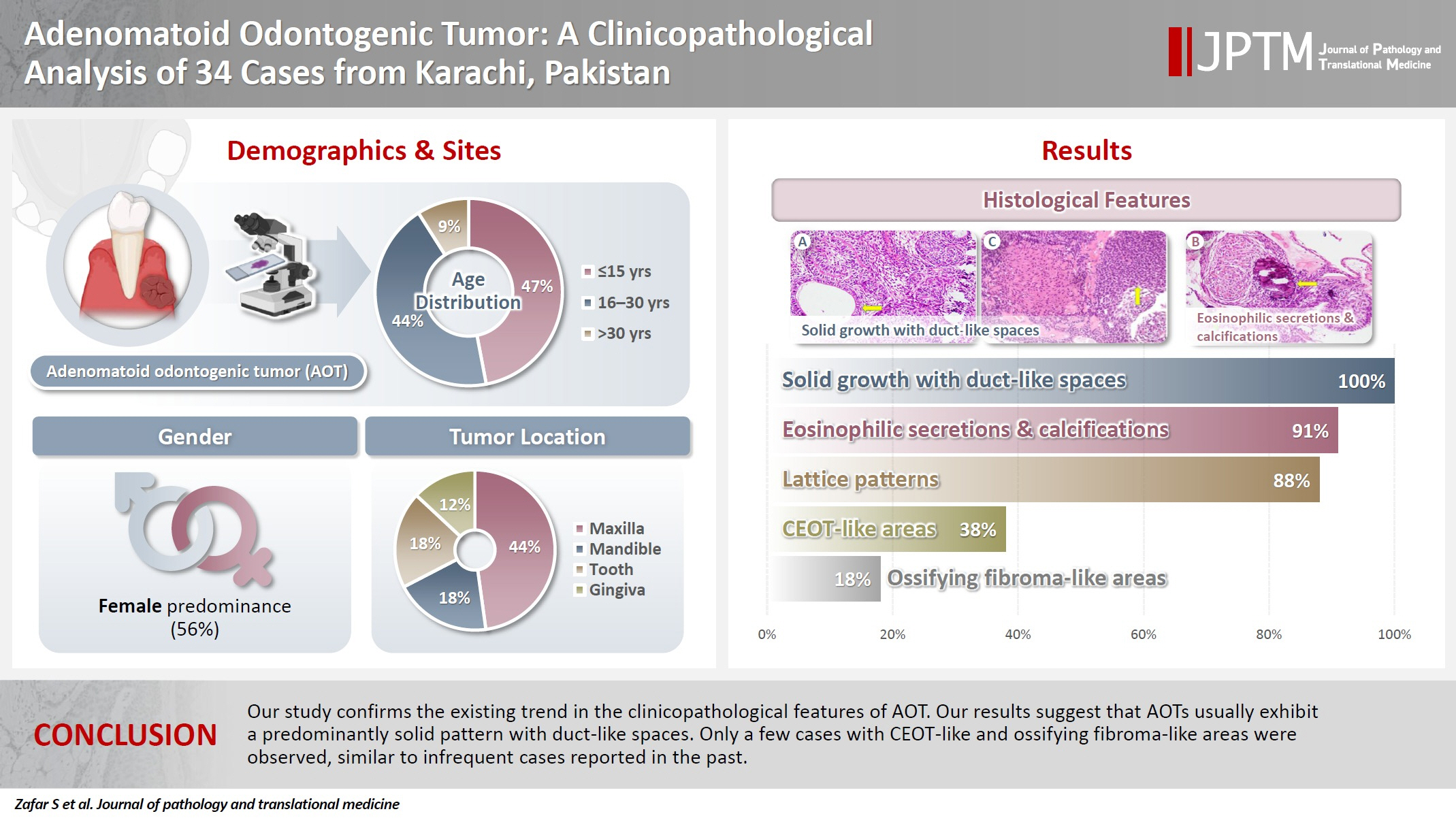

Adenomatoid odontogenic tumor: clinicopathological analysis of 34 cases from Karachi, Pakistan -

Summaya Zafar1

, Sehar Sulaiman1

, Sehar Sulaiman1 , Madeeha Nisar2

, Madeeha Nisar2 , Poonum Khan3

, Poonum Khan3 , Nasir Ud Din1

, Nasir Ud Din1

-

Journal of Pathology and Translational Medicine 2025;59(6):390-397.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4132/jptm.2025.07.11

Published online: October 2, 2025

1Section of Histopathology, Department of Pathology and Lab Medicine, Aga Khan University, Karachi, Pakistan

2Section of Histopathology, Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Combined Military Hospital, Rawalpindi, Pakistan

3Department of Radiology, Aga Khan University, Karachi, Pakistan

- Corresponding Author: Summaya Zafar, MBBS Section of Histopathology, Department of Pathology and Lab Medicine, Aga Khan University, National Stadium Rd, Karachi City, Sindh, Pakistan Tel: +92-3471244479, E-mail: dr.summaiyazafar@gmail.com

© The Korean Society of Pathologists/The Korean Society for Cytopathology

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- 603 Views

- 79 Download

Abstract

-

Background

- Adenomatoid odontogenic tumor (AOT) is a benign slow-growing neoplasm of odontogenic epithelial origin that is relatively uncommon. Only a few studies have described its histological features. Hence, we aimed to describe the clinicopathological features of AOT in a cohort of patients.

-

Methods

- AOT cases diagnosed between 2009 and 2024 were searched electronically. Glass slides were retrieved from archives and were reviewed by two pathologists to record the associated morphological features. Other data including patient demographics and tumor site were collected by reviewing histopathology reports.

-

Results

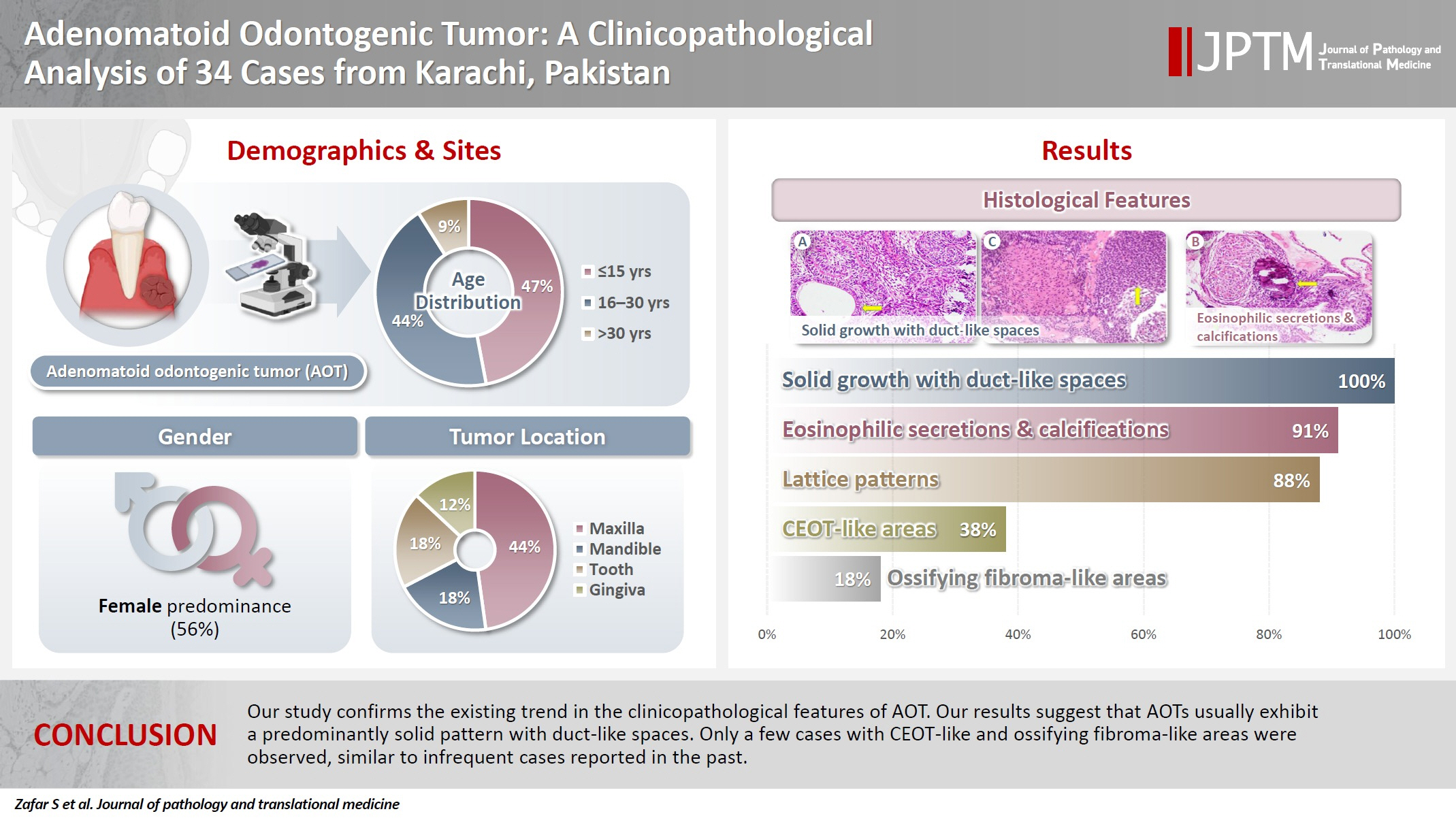

- The age of patients ranged from 9 to 44 years (mean, 17.7 years), and most were female (55.9%). The maxilla (44.1%) was the most common tumor site. Histologically, a predominantly solid growth pattern (n = 34) accompanied by ducts with a cuboidal/columnar epithelial lining (n = 31), eosinophilic secretions (n = 31), calcifications (n = 31), lattice work pattern (n = 30), and cystic areas (n = 20) were observed. Less frequent features included calcifying epithelial odontogenic tumor (CEOT)–like areas (n = 13), osteodentin (n = 6), association with impacted tooth (n = 3), mucin in tubules (n = 7), fibrocollagenous stroma (n = 6), mucin in ducts (n = 3) and ossifying fibroma-like areas (n = 6). The association of ducts with a cuboidal/columnar epithelial lining, lattice work pattern, calcifications, and eosinophilic secretions with gingival tumors was statistically significant (p ≤ .05). Additionally, tooth tumors were significantly associated with CEOT-like areas (p = .03).

-

Conclusions

- Our study confirms the trends in the clinicopathological features of AOT in previous case reports. Our results suggest that AOTs usually exhibit a predominantly solid pattern with duct-like spaces. Only a few cases with CEOT-like and ossifying fibroma-like areas were observed, similar to infrequent cases reported in the past.

- Adenomatoid odontogenic tumor (AOT) is relatively uncommon, representing less than 3% of all odontogenic tumors [1-3]. It is a benign, slow-growing neoplasm of odontogenic epithelial origin [1-3] that originates from the remains of the dental lamina or the enamel organ [1,4-6]. The term “adenomatoid odontogenic tumor” was first coined by Philipsen et al. in 1969 and was later adopted by the World Health Organization [2-5,7,8].

- The three clinical manifestations of AOT are extra-osseous (on the gingiva, often called peripheral; 5% of cases), intra-osseous extra-follicular (present between erupted teeth; 25% of cases), and intra-osseous follicular (associated with impacted teeth; 70% of cases) [1]. The most frequent sites for AOT are the mandible and the anterior maxilla, with the maxilla involved nearly twice as frequently as the mandible [3,9]. Follicular variants are more frequently linked to impacted maxillary canines, accounting for 60% of cases [1,3,10]. Although infrequently reported at sites beyond the premolars, AOT cases have also been observed in the maxilla and posterior mandible. The anterior maxilla accounts for about 53% of cases, while the maxillary premolar area accounts for 9% [11]. Approximately 2% of cases involve the molar region [11]. AOT is more prevalent in females than males, with a nearly 2:1 female-male ratio [1,3,12]. About 70% of AOT cases occur between the ages of 10 and 19, with fewer cases occurring beyond 30 years of age [1]. Clinically, tumors typically have a diameter of 1–3 cm; however, larger tumor diameters have occasionally been observed [1,11].

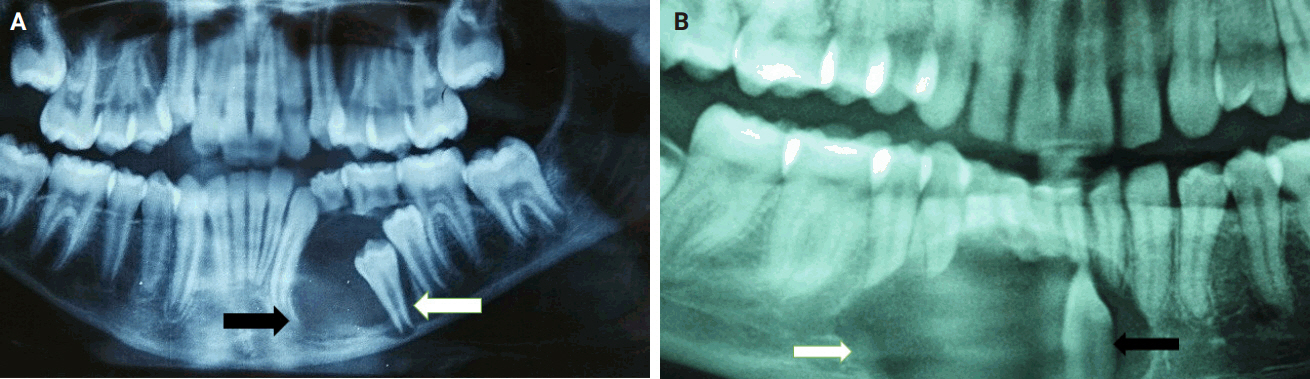

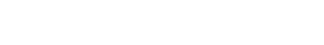

- On radiography, AOT typically presents as well-defined, corticated, unilocular, radiolucent lesions, with 10% or more exhibiting some degree of calcification [9,11,13,14]. Histologically, AOT is composed of cuboidal epithelial cells grouped in duct-like structures with or without calcifications, epithelial spheres or whorls, and strands of spindle-shaped epithelial cells [6,11,13]. The calcifications can be nonspecific or comprise cementum-like globules. Occasionally, globules of homogenous eosinophilic material representing amyloid are observed [6,15]. The thick, fibrous connective tissue capsule supporting these tumors facilitates easy lesion detachment from the tooth and surrounding bone, sometimes allowing the clinician to save the impacted tooth in cases of follicular AOT. Treatment typically involves conservative surgical excision with simple curettage or enucleation [4,9]. Recurrence is exceedingly rare, although a few cases have been reported [3,4,9,16].

- Although a few cases have previously been reported from Pakistan, a comprehensive clinicopathological analysis of a series of AOT cases is lacking. Here, we present the histopathological analysis of AOT cases from a cohort of 34 patients at a single center in Pakistan.

INTRODUCTION

- Study setting and design

- This was a descriptive observational study conducted at the Aga Khan University, Karachi, Pakistan. Histologically proven cases of AOT reported between 2009 and 2024 were electronically retrieved along with the respective hematoxylin and eosin-stained slides. Cases were analyzed in correlation with radiological presentations, including tumor site, relationship to teeth, and other morphological features.

- Data collection and case review

- Data regarding patient demographics were retrieved from the institution’s Integrated Laboratory Management System, including information such as age and sex. The glass slides of all cases were reviewed by two pathologists to record morphological features, including solid growth patterns, eosinophilic secretions, calcifications, lattice work patterns, calcifying epithelial odontogenic tumor (CEOT)–like areas, cystic areas, presence of dentin, ossifying fibroma-like areas, mucin in ducts and tubules, fibrocollagenous stroma, and cuboidal/columnar lining of ducts. Cases that were autolyzed or had suboptimal fixation were excluded from the study. All data were recorded on a standardized proforma.

- Histopathological criteria and classification

- Certain specific and/or diagnostically challenging morphological features were defined to ensure consistency in analysis, as follows: (1) CEOT-like areas were identified by the presence of polyhedral epithelial cells with nuclear pleomorphism, intercellular bridges, and eosinophilic amyloid-like material, often accompanied by concentric calcifications, but distinguished from true CEOT by the absence of infiltrative growth and coexistence with classic AOT features such as duct-like structures and whorled epithelial nests. (2) Ossifying fibroma-like areas were characterized by cellular fibrous stroma containing trabeculae of osteoid or cementum-like calcifications, interpreted as reactive metaplastic ossification rather than neoplastic fibro-osseous proliferation based on the absence of zonal maturation or osteoblastic rimming typical of ossifying fibromas. (3) For cases with overlapping features, classification prioritized predominant histology (≥50% of sampled tissue) and pathognomonic criteria. Lesions retaining encapsulation and ductal architectures despite focal CEOT-like or ossifying fibroma-like patterns were classified as AOT, whereas tumors meeting diagnostic thresholds for ossifying fibroma such as bony trabeculae with osteoblastic activity were excluded.

- Statistical analysis

- For statistical analysis, information from hard copies of the study proformas was entered in Microsoft Excel software (Microsoft Excel 2013 {15.0.5553.1000} 32-bit). Statistical significance for the association of tumor sites with various morphological features was determined using the chi-squared test and expressed as p-values. A p-value of ≤.05 was considered statistically significant. All chi-square tests were performed on 2 × 2 contingency tables. Fisher’s exact test was substituted for expected cell frequencies <5. p-values reflect standalone comparisons and are not adjusted for multiple testing. Other descriptive data were presented as percentages, tables, and figures.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

- A total of 34 cases were diagnosed during the study period. Patient age ranged from 9 to 44 years, with a mean age of 17.7 years. Most patients were in the age group of ≤15 years (47.1%), followed by those aged 16–30 years (44.1%) and >30 years (8.8%). Most cases occurred in females (n = 19) as compared to males (n = 15), resulting in a female to male ratio of 1.3:1. Involvement of the maxilla was common (n = 15, 44.1%) as compared to the mandible (n = 6, 17.7%), tooth (n = 6, 17.7%), gingiva (n = 4, 11.8%), and buccal vestibule (n = 1, 2.9%) (Table 1).

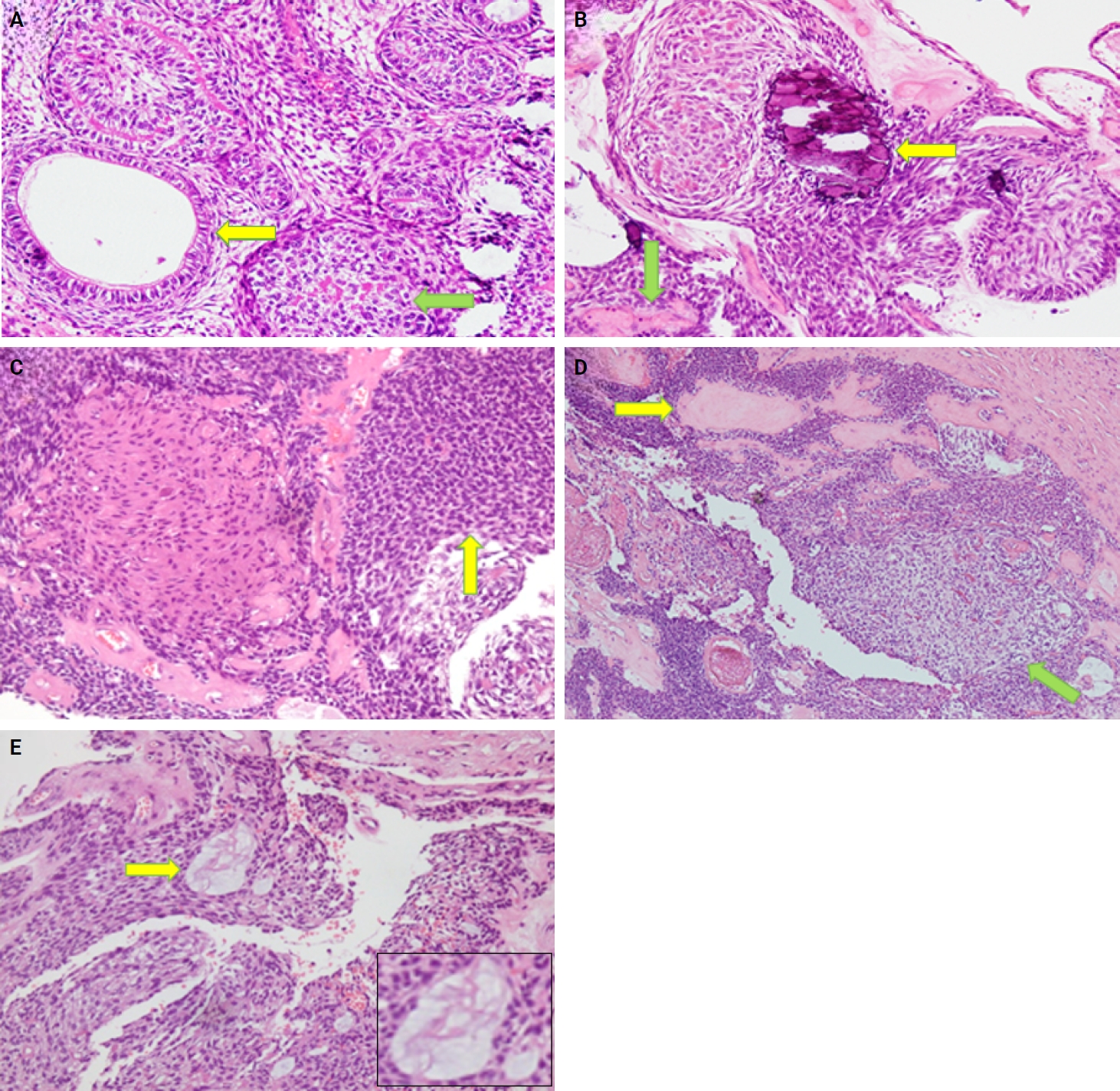

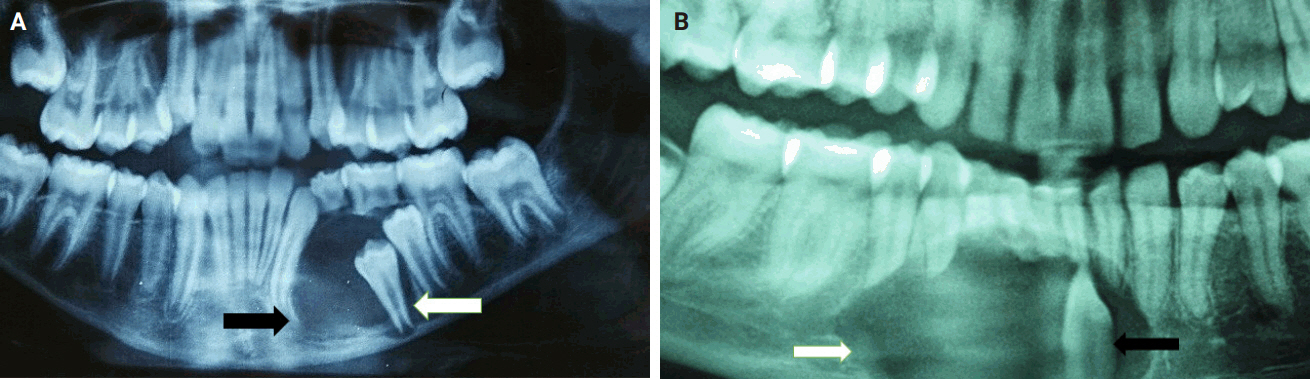

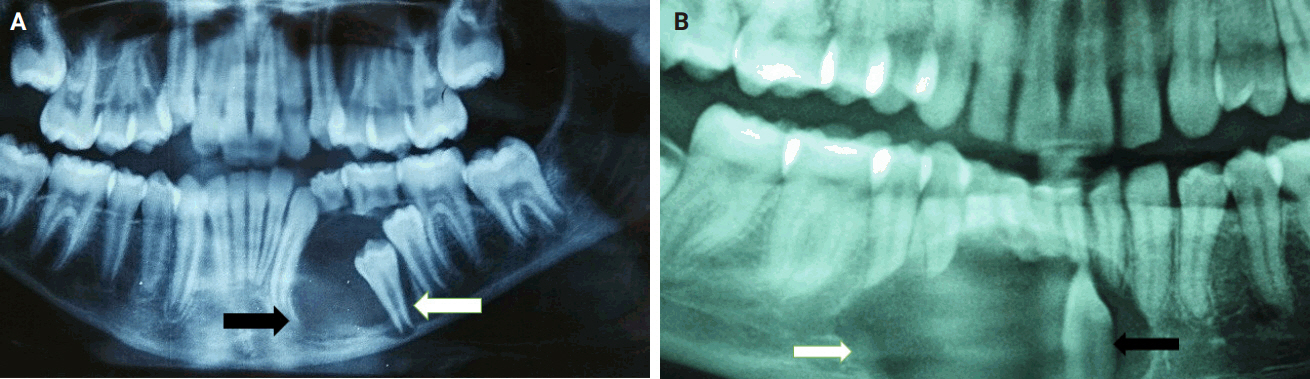

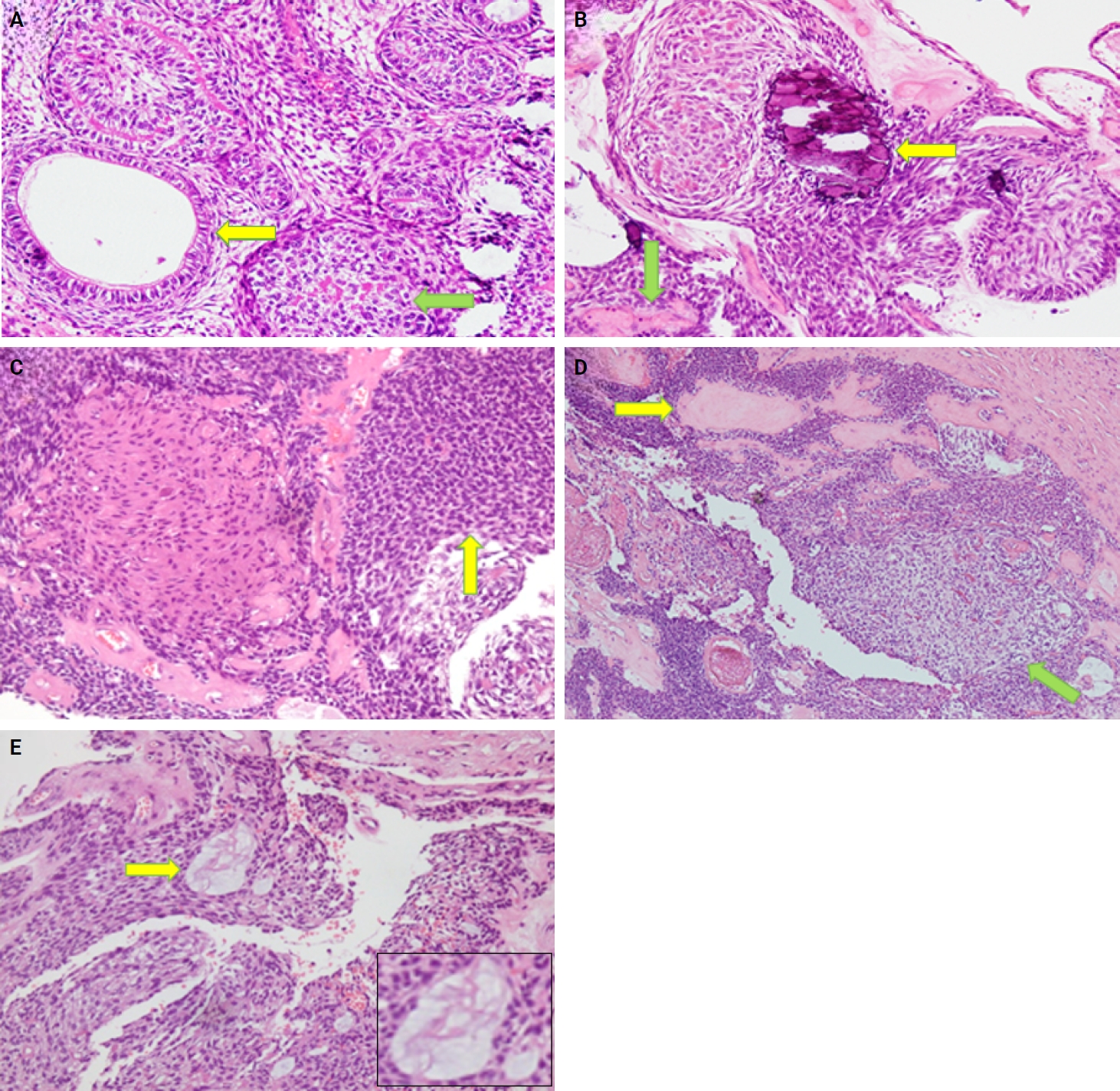

- Almost all cases exhibited typical histopathological findings of AOT: a solid growth pattern (n = 34), accompanied by ducts lined by cuboidal to low columnar epithelial cells proliferating in the form of whorls and nodules (n = 31). The ducts were filled with eosinophilic secretions in 31 cases, and interlacing strands or a lattice work pattern was seen in 30 cases. Psammomatous or dystrophic calcifications were seen in 31 cases. Other morphological findings included cystic areas (n = 20), CEOT-like areas (n = 13), ossifying fibroma-like areas (n = 6), fibrocollagenous stroma (n = 6), and associated osteodentin production (n = 6). Less frequent findings included mucin in ducts (n = 3), and in tubules (n = 7). Radiographically only six cases were associated with impacted teeth (Fig. 1A, B). The morphological features of AOT in relation to different tumor sites is presented in Table 2.

- The association of ducts with a cuboidal/columnar epithelial lining, lattice work pattern, calcifications, and eosinophilic secretions with gingival tumors was found to be statistically significant (p ≤ .05). Additionally, tooth tumors were significantly associated with CEOT-like areas (p = .026) (Table 2).

RESULTS

- AOT, a benign noninvasive odontogenic tumor of epithelial origin, typically affects young people, particularly in their second decade, and is more common in women [1-3]. Our retrospective investigation revealed a predominant occurrence of AOT in the second and third decades of life, with a female predilection (55.9% vs. 44.1%), and the majority of tumors originating in the maxilla (44.1%). Most of our findings are consistent with previous reports from Pakistan and internationally. The mean age of our patients was 17.7 years, close to approximate average of 16 years reported in the literature [1,15]. As reported in other studies, the maxillofacial skeleton is frequently the tumor location, with occurrences in the maxilla nearly twice as common as in the mandible (2:1) [3,9], this ratio was even more pronounced in our study, with a maxilla-to-mandible occurrence ratio of approximately 2.5:1.

- The histological diagnosis of AOT requires careful differentiation from other odontogenic lesions with overlapping features. Dentigerous cysts, the most common clinical mimic, lack the duct-like epithelial structures, rosette formations, and calcification characteristics typical of AOT [1,3,17]. Unlike unicystic ameloblastoma, AOT does not exhibit invasive growth, palisading basal cells, or stellate reticulum-like stroma [13]. Calcifying odontogenic cysts may share radiopaque foci but are distinguished by ghost cell keratinization and the absence of tubular eosinophilic material [1,3]. Radiographically, AOT’s association with impacted canines, unilocular radiolucency with “snowflake” calcifications, and encapsulation contrast with CEOT’s diffuse calcifications and ameloblastic fibro-odontoma’s mixed radiopaque-radiolucent “sunburst” appearance [1,6,17]. Immunohistochemically, AOT’s strong cytokeratin (CK) 14 and CK19 expression aids in differentiation from lesions such as lateral periodontal cysts, which lack these markers [6]. These distinctions underscore the necessity of correlating histology with clinical and radiographic findings to avoid misdiagnosis.

- The histological features in the present study demonstrated a predominantly solid growth pattern with interspersed duct-like structures (100%) (Fig. 2A–C). Although AOT may also exhibit a cribriform pattern to varying degrees alongside the solid growth pattern, cribriform patterns are not characteristic of AOT and have scarcely been reported in the literature [18,19]. The prevalence of duct-like spaces, a prominent finding in AOT, has been abundantly reported in previous research [20,21]. Furthermore, eosinophilic amorphous material or tumor droplets were found in 94.1% of our cases. Similarly, eosinophilic tumor droplets have been observed in almost all cases by Leon et al. [21] and Jivan et al. [22]. It has been demonstrated that tumor droplets in AOTs are immunopositive for enamel proteins, including sheathlin, enamelin, and amelanogenin, suggesting that this material is most likely enamel in nature [23,24]. AOTs have also been shown to have variable quantities of calcified structures [20,21,25]; findings in the present study of psammomatous and dystrophic calcifications in 91.2% of cases support this observation. Some of the tumors exhibited osteodentin (17.6%), confirming the low frequency of this morphological feature (Fig. 2B, D). AOTs have occasionally been observed to contain hyaline, dysplastic material, or calcified osteodentin, sometimes with concurrent abortive enamel [26,27]. Since odontogenic epitomesenchyme is absent from AOTs, Philipsen and Nikai propose that these materials are most likely the product of a metaplastic process and should not be construed as an induction phenomena [25].

- Areas resembling CEOT were observed in less than half of our cases (38.2%); only a few such AOT cases have been reported previously (Fig. 2D). AOT may exhibit areas that resemble CEOT, odontomas in development, and other odontogenic tumors or hamartomas [28,29]. Mosqueda-Taylor et al. [30] emphasize that, in contrast to true CEOT, CEOT-like areas in AOTs do not appear as solid, infiltrative nests. Furthermore, CEOT-like areas in AOTs do not affect the biological activity and developmental capacity of AOTs, nor do they exhibit the characteristic pleomorphism found in the epithelial component of CEOT. Therefore, areas that resemble CEOT should be regarded as normal occurrences within the histomorphological spectrum of AOT [30,31].

- In the present study, cystic areas were observed in 58.8% of cases. AOTs can have cystic regions that mimic odontogenic cysts, such dentigerous cysts [21,32]. Leon et al. [21] reported cystic areas in 56.4% of AOTs. Moreover, 17.6% of our cases exhibited ossifying fibroma-like areas. This finding is unusual and has rarely been reported in the literature [33,34]. In the anterior mandible, Prakash et al. [33] documented the co-occurrence of an ossifying fibroma and a follicular variant of AOT in relation to impacted teeth, despite the two lesions existing independently. According to Li et al. [35], a 22-year-old female had AOT in her right maxilla with a fibro-osseous reaction in the surrounding tissue, as is typical of ossifying fibromas. This case showed cellular fibro-connective tissue with calcifications mimicking ossicles and cementicles, in contrast to the presence of loosely structured stroma in AOT. Instead of treating it as a collision of two distinct lesions, the authors referred to it as a secondary fibro-osseous reaction to AOT as it shared the same biological behavior and prognosis as AOT and was therefore treated conservatively in a manner similar to conventional AOT [35].

- Mucin within the ducts was noted in three cases (16.8%) and within the tubules in seven cases (20.6%) (Fig. 2E). This finding is infrequent and not commonly reported in the published literature. Additionally, only three cases (8.8%) in our study were associated with an impacted tooth. Radiographically, the lesions commonly presented as unilocular radiolucent cysts.

- Regarding treatment and prognosis, conservative surgical enucleation with curettage is the treatment of choice for AOT due to their benign nature and very low recurrence rates [36-38]. This approach generally allows complete bone regeneration without the need for bone grafting, as natural healing is facilitated by preservation of the periosteum [36]. Histologically, cystic variants of AOT characterized by duct-like structures and calcifications have been associated with easier surgical excision, reduced intraoperative bleeding, and faster postoperative healing [38]. For larger lesions, staged management involving fenestration decompression followed by delayed enucleation has been shown to reduce surgical morbidity while maintaining an excellent prognosis without recurrence [36-38]. Although our study did not include data regarding treatment and prognosis, these findings from the literature provide important context for interpreting the clinical significance of histopathological features and support minimally invasive, tooth-preserving treatment strategies with long-term follow-up.

- Our study had a few limitations. Firstly, while this study provides comprehensive clinicopathological data, molecular characterization of KRAS mutations, a hallmark genetic alteration occurring in 71%–76% of AOTs globally, was not performed [39]. Emerging evidence suggests that KRAS mutations, particularly G12V/R at codon 12, drive mitogen-activated protein kinase/ERK pathway activation in AOTs, potentially influencing their indolent behavior [39]. In our current clinicopathological analysis, we did not include molecular profiling due to resource constraints and the retrospective nature of the study. Secondly, the study’s sample size (n = 34) may limit the generalizability of our findings. Low expected frequencies in certain subgroups necessitated the use of Fisher’s exact test, which is more appropriate for sparse data. Nonetheless, the risk of type II errors, wherein true associations may remain undetected, cannot be ruled out. Lastly, we did not evaluate long-term patient prognosis or document specific treatment modalities, such as surgical techniques or adjunct therapies. While the existing literature supports the effectiveness of conservative management, the absence of follow-up data precludes conclusions about recurrence rates in our cohort. To address these limitations, we aim to conduct a future multi-center study on a broader population in Pakistan, prioritizing molecular analyses to evaluate KRAS mutation frequencies and to investigate potential correlations with histopathological features. We also intend to explore the efficacy of specific treatment protocols, and assess long-term patient prognosis through extended monitoring.

- The clinicopathological features of AOTs observed in our investigation are consistent with those frequently reported in the literature. Our findings indicate that AOTs typically affect females, particularly in the second and third decades of life, and characteristically exhibit a solid morphological pattern with duct-like spaces and calcified material as predominant features. Furthermore, ossifying fibroma-like areas in AOTs are very rare, and CEOT-like areas may also be relatively uncommon.

DISCUSSION

Ethics Statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Aga Khan University (Ref # 2024-10499-31005). All patients/legally authorized guardians gave their informed consent for the publication of the respective cases.

Availability of Data and Material

All data generated or analyzed during the study are included in this published article.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: NUD. Data curation: SZ, SS, MN, PK. Formal analysis: SZ. Project administration: NUD. Resources: NUD. Software: SZ, SS. Supervision: NUD. Visualization: SZ, SS, MN. Writing—original draft: SZ. Writing—review & editing: SS, MN, PK, NUD. Approval of final manuscript: all authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no potential conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

No funding to declare.

- 1. More CB, Das S, Gupta S, Bhavsar K. Mandibular adenomatoid odontogenic tumor: radiographic and pathologic correlation. J Nat Sci Biol Med 2013; 4: 457-62. PubMedPMC

- 2. Reddy Kundoor VK, Maloth KN, Guguloth NN, Kesidi S. Extrafollicular adenomatoid odontogenic tumor: an unusual case presentation. J Dent (Shiraz) 2016; 17: 370-4. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 3. Vasudevan K, Kumar S, Vigneswari S. Adenomatoid odontogenic tumor, an uncommon tumor. Contemp Clin Dent 2012; 3: 245-7. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 4. Saluja R, Kaur G, Singh P. Aggressive adenomatoid odontogenic tumor of mandible showing root resorption: a histological case report. Dent Res J (Isfahan) 2013; 10: 279-82. PubMed

- 5. Friedrich RE, Zustin J, Scheuer HA. Adenomatoid odontogenic tumour of the mandible. Anticancer Res 2010; 30: 1787-92. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 6. Seo WG, Kim CH, Park HS, Jang JW, Chung WY. Adenomatoid odontogenic tumor associated with an unerupted mandibular lateral incisor: a case report. J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg 2015; 41: 342-5. PubMed

- 7. Philipsen HP, Birn H. The adenomatoid odontogenic tumour. Ameloblastic adenomatoid tumour or adeno-ameloblastoma. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand 1969; 75: 375-98. ArticlePubMed

- 8. Philipsen HP, Reichart PA. The adenomatoid odontogenic tumour: ultrastructure of tumour cells and non-calcified amorphous masses. J Oral Pathol Med 1996; 25: 491-6. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 9. Baskaran P, Misra S, Kumar MS, Mithra R. Adenomatoid odontogenic tumor: a report of two cases with histopathology correlation. J Clin Imaging Sci 2011; 1: 64.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 10. John JB, John RR. Adenomatoid odontogenic tumor associated with dentigerous cyst in posterior maxilla: a case report and review of literature. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol 2010; 14: 59-62. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 11. Kalia V, Kalra G, Kaushal N, Sharma V, Vermani M. Maxillary adenomatoid odontogenic tumor associated with a premolar. Ann Maxillofac Surg 2015; 5: 119-22. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 12. Yilmaz N, Acikgoz A, Celebi N, Zengin AZ, Gunhan O. Extrafollicular adenomatoid odontogenic tumor of the mandible: report of a case. Eur J Dent 2009; 3: 71-4. Article

- 13. Lee SK, Kim YS. Current concepts and occurrence of epithelial odontogenic tumors: I. Ameloblastoma and adenomatoid odontogenic tumor. Korean J Pathol 2013; 47: 191-202. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 14. Shanmuga PS, Ravikumar A, Krishnarathnam K, Rajendiran S. Intraosseous calcifying epithelial odontogenic tumor in a case with multiple myeloma. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol 2009; 13: 10-3. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 15. Jivan V, Altini M, Meer S, Mahomed F. Adenomatoid odontogenic tumor (AOT) originating in a unicystic ameloblastoma: a case report. Head Neck Pathol 2007; 1: 146-9. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 16. Jindwani K, Paharia YK, Kushwah AP. Surgical management of peripheral variant of adenomatoid odontogenic tumor: a rare case report with review. Contemp Clin Dent 2015; 6: 128-30. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 17. Chakraborty R, Sen S, Goyal K, Pandya D. "Two third tumor": a case report and its differential diagnosis. J Family Med Prim Care 2019; 8: 2140-3. PubMed

- 18. Santos JN, Lima FO, Romerio P, Souza VF. Adenomatoid odontogenic tumor: an unusual case exhibiting cribriform aspect. Quintessence Int 2008; 39: 777-81. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 19. de Matos FR, Nonaka CF, Pinto LP, de Souza LB, de Almeida Freitas R. Adenomatoid odontogenic tumor: retrospective study of 15 cases with emphasis on histopathologic features. Head Neck Pathol 2012; 6: 430-7. ArticlePubMed

- 20. Philipsen HP, Reichart PA. Adenomatoid odontogenic tumour: facts and figures. Oral Oncol 1999; 35: 125-31. ArticlePubMed

- 21. Leon JE, Mata GM, Fregnani ER, et al. Clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of 39 cases of adenomatoid odontogenic tumour: a multicentric study. Oral Oncol 2005; 41: 835-42. ArticlePubMed

- 22. Jivan V, Altini M, Meer S. Secretory cells in adenomatoid odontogenic tumour: tissue induction or metaplastic mineralisation? Oral Dis 2008; 14: 445-9. ArticlePubMed

- 23. Saku T, Okabe H, Shimokawa H. Immunohistochemical demonstration of enamel proteins in odontogenic tumors. J Oral Pathol Med 1992; 21: 113-9. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 24. Takata T, Zhao M, Uchida T, Kudo Y, Sato S, Nikai H. Immunohistochemical demonstration of an enamel sheath protein, sheathlin, in odontogenic tumors. Virchows Arch 2000; 436: 324-9.

- 25. Philipsen HP, Nikai H. Adenomatoid odontogenic tumour. In: Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D, eds. Pathology and genetics of head and neck tumours. Lyon: IARC Press, 2005; 304-5. Article

- 26. Tajima Y, Sakamoto E, Yamamoto Y. Odontogenic cyst giving rise to an adenomatoid odontogenic tumor: report of a case with peculiar features. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1992; 50: 190-3. PubMed

- 27. Takeda Y. Induction of osteodentin and abortive enamel in adenomatoid odontogenic tumor. Ann Dent 1995; 54: 61-3. ArticlePubMed

- 28. Zeitoun IM, Dhanrajani PJ, Mosadomi HA. Adenomatoid odontogenic tumor arising in a calcifying odontogenic cyst. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1996; 54: 634-7. ArticlePubMed

- 29. Dunlap CL, Fritzlen TJ. Cystic odontoma with concomitant adenoameloblastoma (adenoameloblastic odontoma). Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1972; 34: 450-6. ArticlePubMed

- 30. Mosqueda-Taylor A, Carlos-Bregni R, Ledesma-Montes C, Fillipi RZ, de Almeida OP, Vargas PA. Calcifying epithelial odontogenic tumor-like areas are common findings in adenomatoid odontogenic tumors and not a specific entity. Oral Oncol 2005; 41: 214-5. ArticlePubMed

- 31. Montes Ledesma C, Mosqueda Taylor A, Romero de Leon E, de la Piedra Garza M, Goldberg Jaukin P, Portilla Robertson J. Adenomatoid odontogenic tumour with features of calcifying epithelial odontogenic tumour. (The so-called combined epithelial odontogenic tumour.) Clinico-pathological report of 12 cases. Eur J Cancer B Oral Oncol 1993; 29B: 221-4. ArticlePubMed

- 32. Gadewar DR, Srikant N. Adenomatoid odontogenic tumour: tumour or a cyst, a histopathological support for the controversy. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2010; 74: 333-7. Article

- 33. Prakash AR, Reddy PS, Bavle RM. Concomitant occurrence of cemento-ossifying fibroma and adenomatoid odontogenic tumor with bilateral impacted permanent canines in the mandible. Indian J Dent Res 2012; 23: 434-5. Article

- 34. Priya B, Kumar P, Augustine J, Malhotra R, Urs AB. Rare histological presentation of adenomatoid odontogenic tumor: a series of three unique cases. Oral Oncol Rep 2024; 9: 100167.ArticlePubMed

- 35. Li BB, Xie XY, Jia SN. Adenomatoid odontogenic tumor with fibro-osseous reaction in the surrounding tissue. J Craniofac Surg 2013; 24: e100-1. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 36. Handschel JG, Depprich RA, Zimmermann AC, Braunstein S, Kubler NR. Adenomatoid odontogenic tumor of the mandible: review of the literature and report of a rare case. Head Face Med 2005; 1: 3.Article

- 37. Diaz Castillejos R, Maria Nieto Munguia A, Castillo Ham G. Adenomatoid odontogenic tumor: case report and literature review. Rev Odontol Mex 2015; 19: 183-7. Article

- 38. Espinoza V, Ortiz R. Adenomatoid odontogenic tumor: case report and literature review. Res Rep Oral Maxillofac Surg 2021; 5: 050.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 39. Marin C, Niklander SE, Martinez-Flores R. Genetic profile of adenomatoid odontogenic tumor and ameloblastoma: a systematic review. Front Oral Health 2021; 2: 767474.ArticlePubMedPDF

REFERENCES

Figure & Data

References

Citations

PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link-

Cite this Article

Cite this Article

- Cite this Article

-

- Close

- Download Citation

- Close

- Figure

Fig. 1.

Fig. 2.

Graphical abstract

| Characteristic | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (yr) | |

| ≤15 | 16 (47.1) |

| 16–30 | 15 (44.1) |

| >30 | 3 (8.8) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 19 (55.9) |

| Male | 15 (44.1) |

| Tumor site | |

| Maxilla | 15 (44.1) |

| Mandible | 6 (17.7) |

| Gingiva | 4 (11.8) |

| Tooth | 6 (17.7) |

| Buccal vestibule | 1 (2.9) |

| Not specified | 2 (5.8) |

| Total | 34 (100) |

| Morphological feature | Site |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maxilla (n = 15) | Mandible (n = 6) | Gingiva (n = 4) | Tooth (n = 6) | Buccal vestibule (n = 1) | Not specified (n = 2) | |

| Solid growth pattern | 15 (44.1) | 6 (17.6) | 4 (11.8) | 6 (17.6) | 1 (2.9) | 2 (5.9) |

| p-value | .922 | .461 | .424 | .461 | .185 | .185 |

| Eosinophilic secretions | 14 (41.2) | 6 (17.6) | 2 (5.9) | 6 (17.6) | 1 (2.9) | 2 (5.9) |

| p-value | .720 | .720 | .017 | .778 | .458 | .778 |

| Calcifications | 15 (44.1) | 6 (17.6) | 2 (5.9) | 5 (14.7) | 1 (2.9) | 2 (5.9) |

| p-value | .204 | .720 | .017 | .458 | .458 | .778 |

| Lattice work pattern | 14 (41.2) | 6 (17.6) | 2 (5.9) | 6 (17.6) | 1 (2.9) | 1 (2.9) |

| p-value | .424 | .640 | .028 | .640 | .667 | .120 |

| CEOT-like areas | 7 (20.6) | 0 | 0 | 5 (14.7) | 1 (2.9) | 0 |

| p-value | .381 | .026 | .333 | |||

| Cystic areas | 10 (29.4) | 3 (8.8) | 0 | 6 (17.6) | 0 | 1 (2.9) |

| p-value | .424 | .640 | .085 | .778 | ||

| Osteodentin | 2 (5.9) | 1 (2.9) | 1 (2.9) | 1 (2.9) | 0 | 1 (2.9) |

| p-value | .667 | .889 | .667 | .889 | .333 | |

| Impacted tooth | 2 (5.9) | 4 (11.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| p-value | .381 | .458 | ||||

| Ossifying fibroma-like areas | 2 (5.9) | 2 (5.9) | 0 | 2 (5.9) | 0 | 0 |

| p-value | .603 | .333 | .333 | |||

| Mucin in ducts | 2 (5.9) | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.9) | 0 | 0 |

| p-value | .381 | .458 | ||||

| Mucin in tubules | 4 (11.8) | 2 (5.9) | 0 | 1 (2.9) | 0 | 0 |

| p-value | .424 | .333 | .778 | |||

| Fibrocollagenous stroma | 4 (11.8) | 0 | 0 | 2 (5.9) | 0 | 0 |

| p-value | .204 | .333 | ||||

| Ducts with cuboidal/columnar lining | 14 (41.2) | 6 (17.6) | 2 (5.9) | 6 (17.6) | 1 (2.9) | 2 (5.9) |

| p-value | .720 | .720 | .012a | .720 | .458 | .778 |

Values are presented as number (%). AOT, adenomatoid odontogenic tumor; CEOT, calcifying epithelial odontogenic tumor.

E-submission

E-submission