Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > J Pathol Transl Med > Volume 53(4); 2019 > Article

-

Review

How to Foster Professional Values during Pathology Residency -

Yong-Jin Kim,

-

Journal of Pathology and Translational Medicine 2019;53(4):207-209.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4132/jptm.2019.06.12

Published online: June 27, 2019

Department of Pathology, School of Medicine, Kyngpook National University, Daegu, Korea

- Corresponding Author Yong-Jin Kim, MD, PhD Department of Pathology, Kyungpook National University Hospital, 130 Dongdeok-ro, Jung-gu, Daegu 41944, Korea Tel: +82-53-200-5250 Fax: +82-53-426-1515 E-mail: yyjjkim1@gmail.com

• Received: May 31, 2019 • Revised: June 11, 2019 • Accepted: June 12, 2019

© 2019 The Korean Society of Pathologists/The Korean Society for Cytopathology

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

- The importance of professional and ethical behavior by physicians both in training and in practice cannot be overemphasized, particularly in pathology. Professionalism education begins in medical school, and professional attitudes and behaviors are further internalized during residency. Learning how to be a professional is a vital part of residency training. While hospital- or institution-based lecture style educational programs exist, they are often ineffective because the curriculum is not applicable to all specialties, although the basic concepts are the same. In this paper, the author suggests ways for institutions to develop professional attitude assessments and to survey residents’ responses to various unprofessional situations using case scenarios.

- Definitions of professionalism vary across different organizations and fields. Webster’s Dictionary [1] defines professionalism as “a calling requiring specialized knowledge and often long and intensive preparation including instruction in skills and methods as well as in the scientific, historical, or scholarly principles underlying such skills and methods; maintaining by force of organization or concerted opinion high standards of achievement and conduct, and committing its members to continued study and to a kind of work which has for its prime purpose the rendering of a public service.” The American Board of Internal Medicine [2] states that “professionalism in medicine requires the physician to serve the interests of the patient above his or her self-interest. Professionalism aspires to altruism, accountability, excellence, duty, service, honor, integrity, and respect for others.” The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education of the United States [3] has recently mandated that all residency training programs adopt and incorporate competency-based residency training in six defined areas. One of these is professionalism where, among other requirements, residents are expected “to demonstrate a commitment to carrying out professional responsibilities and adherence to ethical principles.” Although the Council expects each training program to develop its own unique approach to incorporating and measuring outcomes in the general competencies, there is little information on how to assess, measure, and teach professionalism, including bioethics. Therefore, much can be gained by sharing information within and across specialty areas, especially in the pathology field.

DEFINITION OF PROFESSIONALISM

- As a medical specialty, pathology deals with the interpretation of changes in human tissues and cells that cause or are caused by disease. In addition to making these diagnoses, pathologists also determine the causes and effects of death and diseases through autopsy and molecular pathology techniques. Pathologists are thus laboratory-based physicians. Issues of medical ethics and professionalism might seem a distant consideration because pathologists do not usually come in direct contact with patients in their daily practice or even during their pathology residency training. One study found that ethical and professionalism issues, such as honesty, recognizing, and reporting medical errors, interpersonal interactions, and conflicts of interest, were some of the most important issues in the pathology profession [4]. While that study involved pathologists already in practice, these concerns and behaviors are just as important for those in training who will soon enter practice. Other professionalism issues that can manifest during residency training include a negative attitude, interpersonal conflicts, or other inappropriate behavior toward staff, peers, faculty, or patients.

- How to teach or foster professionalism during a pathology residency

- First, the concept of professionalism should be added to the “competence of residency” dimension of the educational goals of the Korean Society of Pathology (KSP). The current description of a successful residency states [5]: “Through four years of training courses, residents should acquire the basic concepts of pathology and learn basic knowledge and skills as a pathologist. Residents should handle biopsy as well as cytology specimens by themselves and report accurate and critical diagnoses based on their pathologic findings. In addition, residents should further advance knowledge in at least one concentration during their educational course. Residents should have good communication skills to effectively seek consultations from other physicians regarding the diagnosis and treatment of patients. Residents also have to grow basic yet comprehensive skills to run a laboratory effectively.” We therefore set out to develop KSP educational content for professionalism suitable for pathologists with an emphasis on altruism, accountability, excellence, duty, service, honor, integrity, and respect for others.

- The regular evaluation of a resident’s knowledge, skills, and attitude in this domain of professionalism should be a mandatory part of training. As a result, the resident’s knowledge, attitudes, and skills in this area should show an appropriate evolution during his or her training, with the mastery of more advanced attitudes and skills in being a professional appearing as the resident’s clinical training progresses. Above all, pathology faculty should try to become mentors or role models to residents.

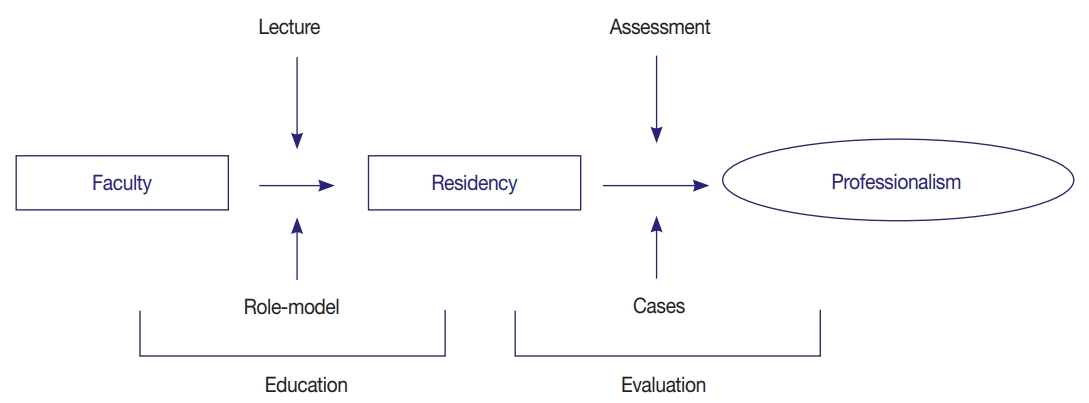

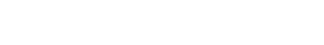

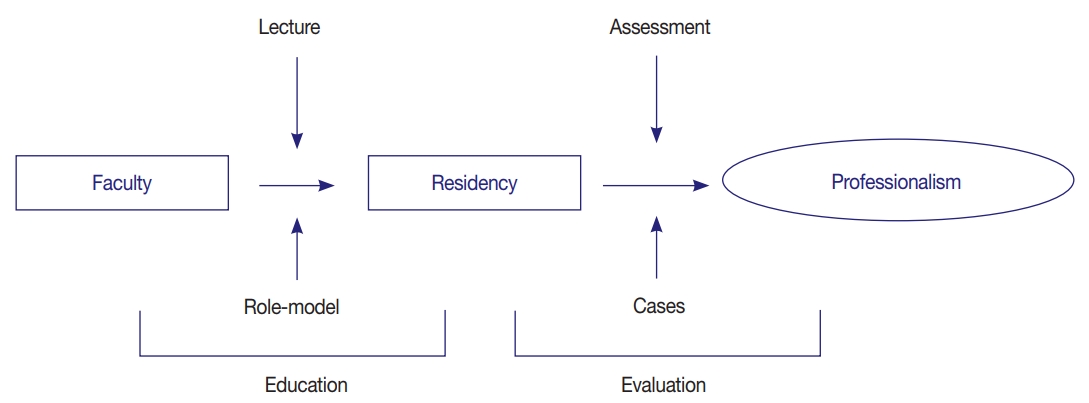

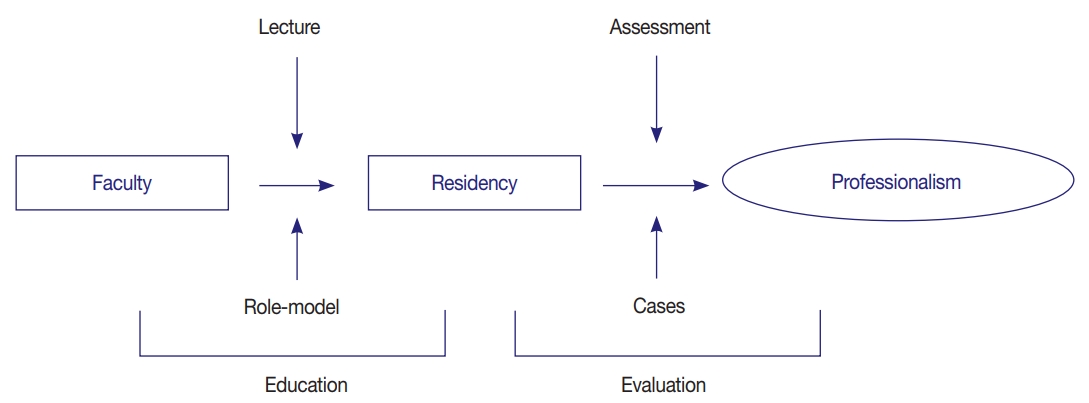

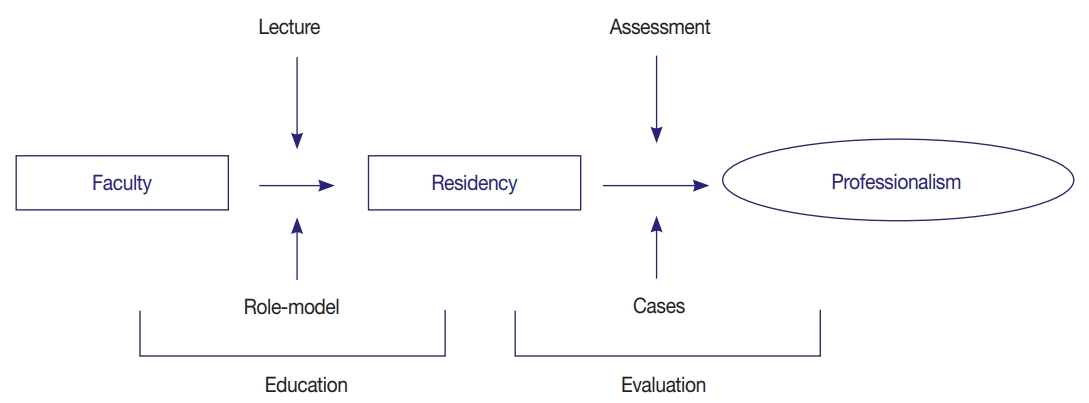

- This paper suggests two practical methods that can be easily applied by the KSP (Fig. 1). One is to make a structured daily assessment in individual departments. The second is for the KSP to modify the case-based evaluation method reported by Domen et al. [6] to conduct a nationwide survey with the goal of self-reflection. Cases should be made by pathologists and reflect current teaching circumstances. The following are assessment forms used at McGill University [7] that can be modified to suit each institute. The author would like to suggest creating a similar evaluation form that can be assessed by education program directors after a trial period.

- Professionalism evaluation items on in-training assessment forms

- Judges whether the trainee is dependable, reliable, honest, and forthright in all information and facts.

- Assesses whether the trainee is able to understand and be sensitive to issues related to age, gender, culture, and ethnicity.

- Determines whether the trainee adequately accepts professional responsibilities, places the needs of the patients before the trainee’s own, and ensures that the trainee or his/her replacement are at all times available to the patient. The trainee is punctual and respects local regulations related to the performance of his/her duties.

- Judges that the trainee maintains a focus on patient care with compassion and empathy.

- Decides whether the trainee is able to self-assess his/her limits of competence and is able to seek and give assistance when necessary.

- Assesses the trainees’ understanding of the principles and practice of biomedical ethics as it relates to the specialty. The trainee practices in an ethically responsible manner.

- Case-based evaluation

- Domen et al. [6] developed five case scenarios highlighting various unprofessional behaviors. A standard set of responses was offered to the participants; polling results were collected electronically, and the results were compared. The cases involved poor attendance, lack of attention, an alcohol odor on the breath, medication effects, dishonesty, poor interpersonal skills, unprofessional use of social media, illegal access to electronic medical records, etc. A level of generational differences appeared to be evident in this study regarding the recognition and management of unprofessional behavior; there was also agreement in some cases. These differences regarding professionalism for both faculty and residents should be considered an integral part of any educational and management approach to professionalism. Presenting or discussing appropriate actions for each scenario provides students with opportunities to recognize a variety of perspectives. The author suggests designing similar local scenarios based on a comparative analysis of residents and faculty to develop supplementary content for professionalism training.

PROFESSIONALISM IN PATHOLOGY

Integrity and honesty

Sensitivity and respect for diversity

Self-disciplined responsibility

Communication with other clinicians

Recognition of one’s own limitations, seeking advice when needed

Understanding the principles of ethics as applied to clinical situations

- The importance of professionalism in the practice of medicine has increased and become a vital part of residency training. While hospital based lecture style educational programs exist, they are often ineffective because the curriculum is not applicable to pathology residency, although the basic concepts are the same. In this paper, the author suggests two practical methods to foster professional values during pathology residency. One is to make a structured daily assessment in individual departments. The second is to conduct a nationwide case-based evaluation by KSP.

CONCLUSION

Fig. 1.Suggested educational methods to use to foster professional values during a pathology residency.

- 1. Gove PB. Webster’s third international dictionary of the English language. Springfield: Merriam-Webster, 1981.

- 2. Project professionalism [Internet]. Philadelphia: American Board of Internal Medicine, 2019 [cited 2019 May 10]. Available from: https://medicinainternaucv.files.wordpress.com/2013/02/project-professionalism.pdf.

- 3. Domen RE, Talbert ML, Johnson K, et al. Assessment and management of professionalism issues in pathology residency training: results from surveys and a workshop by the Graduate Medical Education Committee of the College of American Pathologists. Acad Pathol 2015; 2: 2374289515592887.PubMedPMC

- 4. Domen RE. Ethical and professionalism issues in pathology: a survey of current issues and educational efforts. Hum Pathol 2002; 33: 779-82. PubMed

- 5. Competency of pathology resident [Internet]. Seoul: The Korean Society of Pathologists, 2019 [cited 2019 May 10]. Available from: http://www.pathology.or.kr/html/?pmode=subpage&MMC_id=220&spSeq=35.

- 6. Domen RE, Johnson K, Conran RM, et al. Professionalism in pathology: a case-based approach as a potential educational tool. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2017; 141: 215-9. PubMed

- 7. Snell L. Teaching professionalism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008; 246-62.

REFERENCES

Figure & Data

References

Citations

Citations to this article as recorded by

- A Scoping Review of Professionalism in Neurosurgery

William Mangham, Kara A. Parikh, Mustafa Motiwala, Andrew J. Gienapp, Jordan Roach, Michael Barats, Jock Lillard, Nickalus Khan, Adam Arthur, L. Madison Michael

Neurosurgery.2024; 94(3): 435. CrossRef - A modified Delphi approach to nurturing professionalism in postgraduate medical education in Singapore

Yao Hao Teo, Tan Ying Peh, Ahmad Bin Hanifah Marican Abdurrahman, Alexia Sze Inn Lee, Min Chiam, Warren Fong, Limin Wijaya, Lalit Kumar Radha Krishna

Singapore Medical Journal.2024; 65(6): 313. CrossRef

PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link-

Cite this Article

Cite this Article

- Cite this Article

-

- Close

- Download Citation

- Close

- Figure

How to Foster Professional Values during Pathology Residency

Fig. 1. Suggested educational methods to use to foster professional values during a pathology residency.

Fig. 1.

How to Foster Professional Values during Pathology Residency

E-submission

E-submission