Diagnostic value of cytology in detecting human papillomavirus–independent cervical malignancies: a nation-wide study in Korea

Article information

Abstract

Background

Human papillomavirus (HPV) independent cervical malignancies (HPV-IDCMs) have recently been classified by the World Health Organization (WHO) 5th edition. These malignancies have historically received limited attention due to their rarity and the potential for evasion of HPV-based screening.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed 5,854 biopsy-confirmed cervical malignancies from 22 institutions over 3 years (July 2020–June 2023). Histologic classification followed the WHO guidelines. HPV independence was confirmed by dual negativity for p16 and HPV; discordant cases (p16-positive/HPV-negative) underwent additional HPV testing using paraffin-embedded tissue. Cytological results were matched sequentially to histological confirmation.

Results

The prevalence of HPV-IDCM was 4.4% (257/5,854) overall and was 3.6% (208/5,805 cases) among primary cervical malignancy. Patient age of HPV-IDCM was 29 to 89 years (median, 57.79). Its histologic subtypes included primary adenocarcinoma (n = 116), endometrial adenocarcinoma (n = 35), squamous cell carcinoma (n = 72), metastatic carcinoma (n = 14), carcinoma, not otherwise specified (n = 10), neuroendocrine carcinoma (n = 3), and others (n = 7). Among 155 cytology-histological matched cases, the overall and primary Pap test detection rates were 85.2% (132/155) and 83.2% (104/125), respectively. The interval between cytology and histologic confirmation extended up to 38 months.

Conclusions

HPV-IDCMs comprised 3.6% of primary cervical malignancies with a high detection rate via cytology (83.2%). These findings affirm the value of cytological screening, particularly in patients with limited screening history or at risk for HPV-independent lesions, and may guide future screening protocols.

INTRODUCTION

The Papanicolaou (Pap) test has markedly contributed to the global reduction in the incidence and mortality rates of cervical cancer. In the United States, the number of new cervical cancer cases per 100,000 individuals declined from 14.81 in 1975 to 6.67 in 2018 [1-3]. In South Korea, the incidence rate decreased from 9.2 to 6.2 per 100,000, and the mortality rate fell from 3.4 to 2.5 per 100,000 population between 2001 and 2022 [4].

With increasing recognition of the role of persistent high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) infection in cervical carcinogenesis, HPV testing has become a primary screening modality in many Western countries [5-7]. In 2014, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the cobas HPV test (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland) as a stand-alone screening method for women aged 25 and older [8-10].

This shift has been accelerated by the widespread adoption of HPV vaccination. The efficacy of the HPV vaccines in preventing high-grade cervical lesions has been well established. A nationwide Swedish study (2006–2017) reported incidence rates of 0.51, 0.37, and 0.1 per 100,000 for unvaccinated individuals, those vaccinated between 17-30, and those vaccinated before age 17, respectively [11]. Since 2012, the Korean national immunization program has included HPV vaccination for girls under 13 years of age [12].

The 5th edition of the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of Female Genital Tumors formally recognizes HPV-independent cervical malignancies (HPV-IDCMs) and their precursor lesions in both squamous and glandular categories [13]. The 5 recognized glandular subtypes include gastric, clear cell, mesonephric, endometrioid, and not otherwise specified (NOS). According to the WHO classification, HPV-independent tumors account for approximately 5%–7% of squamous cell carcinomas (SqCCs) and up to 20% of adenocarcinomas. Emerging HPV-independent neoplasms include intraepithelial neoplasia, SqCC, and precursor lesions associated with uterine prolapse and lichen planus (LP) [14-17].

In Japan, the overall prevalence of gynecologic tumors has changed, with rising rates of endometrial and ovarian carcinomas and declining cervical carcinoma rates [18]. Similarly, Taiwan has reported a proportional increase in adenocarcinomas relative to SqCC [19]. In Korea, the most recent data (2024) show a histological distribution of 60.9% SqCC and 23.1% adenocarcinoma [20].

The primary aim of this study was to assess the prevalence rate of HPV-IDCM and to evaluate the diagnostic utility of the Pap test during this period of dynamic screening practices and histologic trends.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data collection

A nationwide study of biopsy–proven cervical malignancies was conducted at 22 institutions across South Korea over 3 years (July 2020 to June 2023). All contributors were actively practicing gynecologic cytopathologists. A total of 5,854 cases were collected along with clinical data including patient age, specimen type, and survival status. Histological subtypes were classified according to the WHO classification of female genital tumors, 5th edition. HPV independence was determined by negativity for both p16INK4a (CDKNA2A) immunohistochemistry and HPV testing. For p16-positive and HPV-negative cases, additional HPV real-time PCR testing (Allplex HPV Detection, Seegene, Seoul, Korea) was performed using paraffin blocks (silica-membrane technology (QIAamp), Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Highly sensitive molecular techniques for detecting HPV DNA or mRNA were not available for this study.

Cytological-histological correlation

Cytological findings were reviewed sequentially, based on temporal relationship to the histological confirmation. Among multiple cytology reports, the report most relevant to the histologic outcome was selected. Cytological diagnoses were classified according to the Bethesda System, 3rd edition. Detection rates included diagnoses of atypical squamous cells, undetermined significance (ASC-US), and atypical glandular cells, undetermined significance (AG-US) or higher.

Interval to final diagnosis

The interval between a significant cytological diagnosis and the initial histological diagnosis was assessed. Cases with an interval longer than 6 months were classified as delayed diagnoses.

RESULTS

Sample characteristics

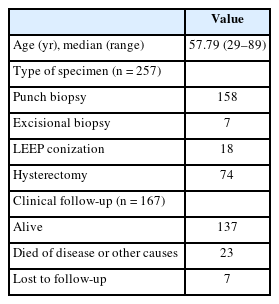

Overall, HPV-IDCM account for 4.4% (257/5,854) of all cases and 3.6% (208/5,805) of primary cervical malignancies (Fig. 1). Patient age of HPV-IDCM ranged from 29 to 89 years, with a median of 57.79 years. Of the 257 cases, the most common specimen type was punch biopsy (n = 158), followed by hysterectomy (n = 74), loop electrosurgical excision procedure conization (n = 18), and other excisions (n = 7). Among the 167 patients with available follow-up data, 137 were alive, 23 had died (due to disease or other causes), and seven were lost to follow-up (Table 1).

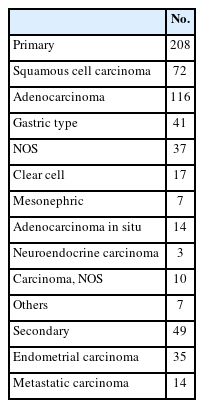

Histologic types of HPV-IDCM

Histologic subtypes were as follows; primary adenocarcinoma (n = 116), which comprised gastric (n = 41), NOS (n = 37), clear cell (n = 17), mesonephric (n = 7), adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS) (n = 14); endometrial adenocarcinoma (n = 35); SqCC (n = 72); metastatic carcinoma (n = 14); carcinoma, NOS (n = 10); neuroendocrine carcinoma (n = 3); and other histological malignancies (n = 7) (Table 2).

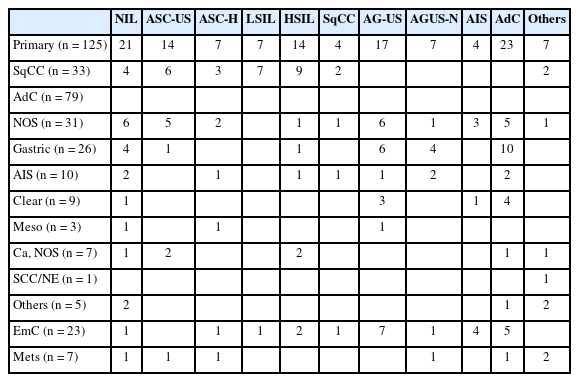

Cyto-pathologic correlation

Among 155 cytology-histological matched cases, the overall/primary Pap test detection rate were 85.2% (132/155) and 83.2% (104/125) (Table 3). A case of 86-year-old women was cytologically evident SqCC. However, two times of real-time HPV-PCR test failed to demonstrate the HPV dependency. The subsequent biopsy showed invasive squamous carcinoma (Fig. 2). Despite the fact that no HPV relationship has been supported, the cytological abnormality has been detected in 29 out of 33 SqCCs (88%). In adenocarcinoma group, the cytological detection rate was 82.2% (65/79 cases).

A representative case of human papillomavirus–independent squamous cell carcinoma with cytohistologic and p16 immunohistochemical findings. (A) The cytological findings showed many atypical squamous cells with high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio, hyperchromatic nuclei, irregular nuclear contour, prominent 2–3 nucleoli, and dense hyperkeratotic cytoplasms (Pap test). (B) p16 immunocytochemical staining failed to demonstrate nuclear-cytoplasmic expression. (C) The scanning view of punch biopsied tissue revealed infiltrating nests with thick keratin pearl (inset). (D) Some irregular atypical squamous nests invaded to stroma (red arrows). (E) p16 immunohistochemistry failed to demonstrate a block positivity.

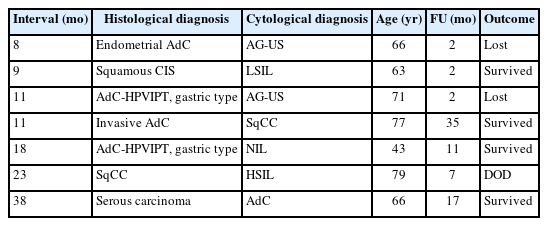

Interval of final histological diagnosis

Of the matched cases, 148 (95.5%) received histological confirmation within 6 months, while seven cases experienced diagnostic delays from 7 to 38 months (Table 4). In our cohort, one patient with gastric-type adenocarcinoma had three abnormal cytology reports (AG-US, favor neoplastic and 2 times of ASC-H [atypical squamous cells, cannot exclude high-grade intraepithelial lesion]) and two negative HPV tests before a definitive diagnosis was made via hysterectomy 11 months later. (Fig. 3)

A chronological sequence of delayed (11 months) diagnosis in a 71-year-old woman with human papillomavirus (HPV) independent cervical malignancies. (A) Three-dimensional cluster of atypical hyperchromatic nuclei are seen, suggestive of atypical glandular cells, undetermined significance favor neoplastic (AGUS-N) (2022-07-18). (B) No definite abnormality is identified in punch biopsied tissue (2022-08-01). (C) No glandular/squamous epithelial dysplasia was identified in loop electrosurgical excision procedure conization (2022-08-11). (D) A cluster of atypical epithelial cells with abundant dense cytoplasm are seen, atypical squamous cells cannot excluded high-grade intraepithelial lesion (ASC-H) (2022-09-26). (E) Overlapping clusters of atypical epithelial cells with hyperchromatic nuclei and dense cytoplasm were seen, ASC-H (2023-01-30). (F, G) The hysterectomy specimen showed a deeply invading atypical glands through the full thickness of the uterine cervical wall. The tumor is composed of gastric type–glands (2023-06-13).

DISCUSSION

In recent years, global cervical cancer screening has increasingly shifted toward primary HPV testing [1-3]. In 2014, the US FDA approved the cobas HPV test (Roche Diagnostics) for stand-alone cervical cancer screening in women aged ≥25 years [8-10].

Despite this, a 2017 survey by the College of American Pathologists reported that nearly 60% of responding laboratories did not offer stand-alone primary HPV testing, concerns about the efficacy of cytology co-testing strategies [19,21,22].

Our study aimed to assess the role of cytology in detecting HPV-independent precursors and malignancies. Recent literature highlights the presence of HPV-negative SqCC and precursor lesions. These cases showed frequent p16 negativity, nuclear p53 overexpression, and diverse genetic alterations (including PIK3CA, STK11, TP53, SMARCB2, and GNAS) along with the consistent presence of the Q472H germline polymorphism in the KDR gene and chromosome 3q gain [14]. HPV-negative precursors showed TP53-mutated differentiated cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and p53 wild-type verruciform intraepithelial neoplasia based on next-generation sequencing data [15].

LP-associated HPV–independent SqCC of the vulva and vagina has also been reported [16], accounting for approximately 70% of vulvar SqCCs. The largest study to date has reported 38 cases of LP-associated SqCC and vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia.

Additionally, a recent study described HPV-independent/p53-abnormal keratinizing SqCC associated with uterine prolapse. Cytological features of SqCC include prominent keratinizing, clear glycogen-rich cytoplasm, and some intracytoplasmic mucin [17].

According to the WHO, HPV-independent invasive cervical SqCC accounts for approximately 5%–7% of all cases [11]. At least 90.9% of HPV-negative lesions were flagged by abnormal cytology [23]. Although large-scale cohort studies are lacking, HPV-negative squamous lesions appear prone to delayed histologic confirmation, particularly in case with indeterminate abnormal cytological findings (ASC-US, ASC-H, low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion). In our series, one patient with high-grade intraepithelial lesion cytology experienced a 23-month delay before histologic diagnosis and subsequently died from disease, underscoring the importance of timely cytological evaluation.

HPV-independent adenocarcinomas represent a minority of endocervical adenocarcinomas. According to the WHO 5th edition, HPV-independent adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix include AIS, gastric type, clear cell type, mesonephric type, and NOS [11]. In our primary cohort, gastric-type adenocarcinoma was the most common subtype (41/116 cases). These tumors were associated with aggressive behavior including destructive invasion, extrauterine spread, and advanced-stage diagnosis [24,25].

Cytologically, gastric-type adenocarcinomas may appear morphologically subtle, mimicking benign cervical glands with a low nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio [26]. Gastric-type adenocarcinoma accounts for nearly 20% of all cervical adenocarcinomas in Japan. A low detection rate was observed via cytology due to the high location of lesion in endocervical canal and bland morphology [27].

Endometrial carcinomas comprise the majority of HPV-negative lesions in our matched cohort. Karaaslan et al. [23] reported that 78.8% of HPV-negative cervical malignancies were endometrial in origin. In our cohort, 22 of 23 endometrial carcinomas were detected cytologically, although the precise diagnostic role of cytology remains unclear due to high stage/grade and concurrent endometrial sampling.

Seven cases in our study experienced histologic diagnostic delays exceeding 6 months, including two cases each of gastric-type adenocarcinomas, squamous (or in situ) carcinomas, and endometrial or serous carcinoma, as well as 1 adenocarcinoma, NOS. This study is limited for a statistically significant difference between HPV dependent vs. independent tumor groups for a diagnostic delay due to no control data.

HPV-negative lesions represent a blind spot in primary HPV-based screening systems, because these cases may escape detection. The impact of high-risk–HPV DNA–based screening on HPV-independent malignancies remains questionable [28]. Missed cases were overlooked due to their small subset. In our cohort, 3.6% of primary cervical cancers were HPV negative proportion that may increase with the rising incidence of adenocarcinoma and the impact of HPV vaccination. In Japan, HPV-negative CIN2+ or adenocarcinoma has not been considered a major barrier to the implementation of HPV-based screening; however, a new nationwide management algorithm has recently been proposed [29].

This study has a limitation that HPV-IDCM cannot exclude an undetectable subtype, which are not included in HPV genotypes as well as no supportive RNA works. The incidence of HPV typing-negative cervical cancer has been reported as 5%–30% with different HPV detection methods [30]. The cytology-histologic matching case are too small volume for an overall detection rate. The clinical outcome was also limited for evidence of poorer outcomes than HPV-dependent group due to no control group.

In summary, HPV-IDCM accounted for 3.6% of primary cervical malignancies, with a cytology (Pap test) detection rate of 83.2%. These findings underscore the ongoing importance of cytological evaluation, particularly in patients with limited screening history or at risk for HPV independent lesions. This evidence may contribute to future refinements in cervical cancer screening strategies.

Notes

Ethics Statement

All procedures performed in the current study were approved by the institutional review boards (IRB) of all participating institutions following the Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. Waiver of the informed consent can only be granted by the appropriate IRB. Formal written informed consent was not required with a waiver by the appropriate IRB or national research ethics committee. The approvals were granted by the following ethics committees: Sanggye Paik Hospital (IRB approval number: SGPAIK2024-04-011; date: April 30, 2024), Soonchunhyang University Seoul Hospital (IRB approval number: 2024-04-012-002), Chungbuk National University (IRB approval number: 2024-05-003), Busan Paik Hospital (BPIRB approval number: 2024-04-030), Kangbuk Samsung Hospital (IRB approval number: KBSMC 2024-05-028-001), Chosun University Hospital (IRB approval number: CHOSUN2024-04-012), Eunpyeong St Mary’s Hospital (IRB approval number: PC24RIDI0058), and Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (IRB approval number: B-2505-973-103).

Availability of Data and Material

The datasets generated or analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: HJK. Data curation: HJK. Formal analysis: HJK, HRJ, JYK, HEP, YJS, SSL. Investigation: HJK, HRJ, JYK, HEP, YJS, SSL. Funding acquisition: HJK, HRJ, JYK, HEP, YJS, SSL. Methodology: HRJ, JS, CWY, ENK, CL, KK, HL, YL, JK, SJJ, JYK, HEP, THK, WL, MSC, RH, YJC, YSL, YC, SRL, MK, YJS, YJH, HJK. Project administration: HJK, HRJ, JYK, HEP, YJS, SSL. Supervision: YJC, SSL. Validation: HJK, HRJ, JYK, HEP, YJS, SSL. Writing—original draft: HJK. Writing—review & editing: HJK, YJC, SSL. Approval of final manuscript: all authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no potential conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

This research was supported in part by The Korean Society for Cytopathology (Grant No. 23-01), Republic of Korea.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the cooperation and scholarly discussions provided by members of the Korean Society of Cytopathologists during the course of this study.