Clinicopathological characteristics of digestive system angioleiomyomas: case report and literature review

Article information

Abstract

Angioleiomyomas are benign soft tissue tumors originating from the vascular wall. Although angioleiomyomas mainly occur in extremities, followed by head, neck, and trunk, they can also be found throughout the digestive system and especially in the oral cavity. Herein, the fourth case of a rectal angioleiomyoma in the English literature is reported and the clinicopathological features of digestive system angioleiomyomas were investigated. In contrast to their soft tissue counterparts, digestive system angioleiomyomas mainly affect males at a slightly younger age. Angioleiomyomas are mainly asymptomatic and only rarely elicit pain. Clinicians consider angioleiomyomas infrequently and instead include more common soft tissue or epithelial tumors in their differential diagnosis. To prevent angiomyolipoma misdiagnosis, pathologists should exercise caution when examining an angioleiomyoma composed of adipose tissue, smooth muscle, and blood vessels. Pathologists, radiologists, and surgeons should be aware that angioleiomyomas can occur in the digestive system.

INTRODUCTION

Angioleiomyomas are benign neoplasms arising from the smooth muscle layer (tunica media) of the blood vessel wall, accounting for 5% of all benign soft tissue neoplasms. Angioleiomyoma typically present as a slow-growing and painful nodule in the extremities of females in their fourth to sixth decade of life. The trunk, head, and neck region can be affected, although less frequently [1,2]. Three histological forms of angioleiomyomas have been described: solid, cavernous, and the less frequent venous form that typically affects the head and neck area, including the oral cavity [2,3].

Although uncommon, angioleiomyomas in the digestive system have been documented in an increasing number of reports. Most of the reported cases involve the oral cavity; however, any part of the alimentary tract can be affected. Herein, a rare case of an incidentally found rectal angioleiomyoma is presented and a comprehensive review of the English literature regarding angioleiomyomas in the gastrointestinal tract with respect to their epidemiological, clinical, and histopathological features provided.

CASE REPORT

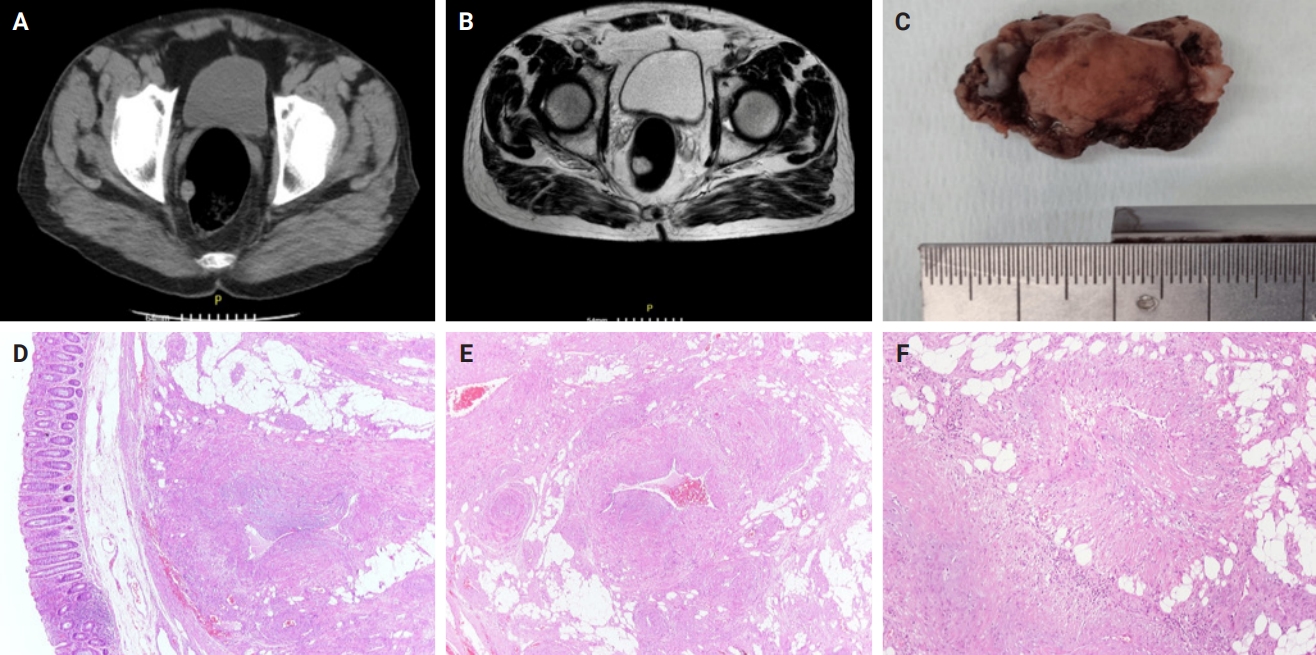

A 68-year-old male was admitted to the Surgical Department for a scheduled repair of an incisional hernia resulting from a surgery for a perforated ulcer of the upper gastrointestinal tract performed two decades ago. The patient was asymptomatic, with no complaints of pain, mass effect, or gastrointestinal bleeding. Both physical examination and routine laboratory tests were unremarkable. During the preoperative computed tomography (CT) scan, a round-shaped lesion 16 mm in size was revealed in the rectal wall, 7 cm from the anal verge (Fig. 1A). Further investigation with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a high signal intensity, lobular/polypoid lesion measuring 21 × 18 mm on the posterolateral rectal wall, projecting into the lumen, with equivocal invasion of the muscular layer (Fig. 1B). The endoscopy showed an intraluminal protrusion covered by an unremarkable mucosa. Clinicians suspected a gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST). An endoscopic submucosal dissection, sparing the muscularis propria, was performed and the specimen was sent to pathology.

Preoperative computed tomography scan (axial plane) showing an incidentally discovered round-shape lesion in the rectal wall (A) characterized by high signal, limitation in perfusion, and prominent enhancement on magnetic resonance imaging (T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging) (B). The macroscopic examination shows a nodule measuring 20 × 13 mm located submucosally (C) confirmed based on histologic examination (D). The neoplasm is composed of thick-walled vessels, intervascular spindle cells with smooth muscle features and mature adipose tissue (E). The neoplastic cells are arranged in bundles proliferating from vascular walls (F).

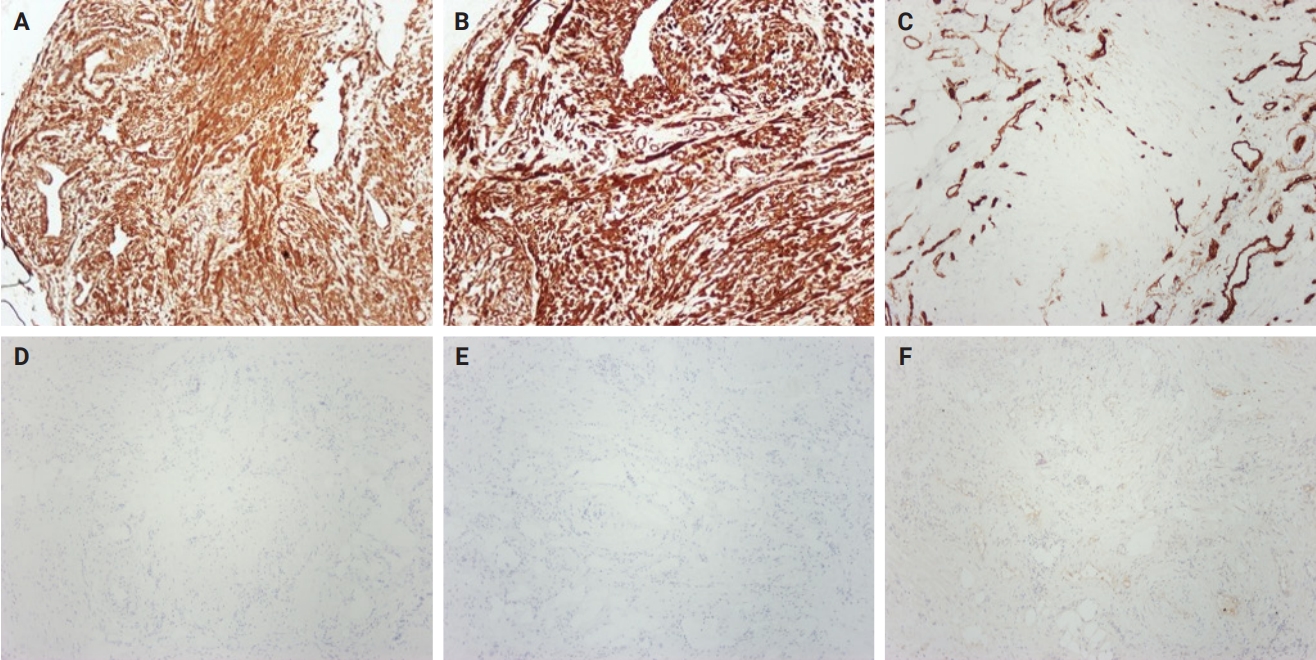

The macroscopic examination revealed a nodular lesion measuring 20 × 13 mm covered by an unremarkable mucosa (Fig. 1C), occupying the submucosal and muscular layers (Fig. 1D). Hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections showed spindle-shaped neoplastic cells, arranged in bundles, proliferating from vascular walls (Fig. 1E, F). Neoplastic cells showed minimal atypia without any mitotic activity. A minor component of mature adipose tissue was observed intermixed with spindle-shaped cells. Immunohistochemical study showed neoplastic cells positive for smooth muscle actin (Fig. 2A), caldesmon (Fig. 2B), and desmin antigens. Immunostains for CD34 (Fig. 2C), HMB-45 (Fig. 2D), MelanA (Fig. 2E), CD117, DOG-1 (Fig. 2F), and S-100 were negative. Histologic and immunohistochemical features were consistent with angioleiomyoma of the rectum, venous type.

DISCUSSION

Angioleiomyomas of the digestive system are extremely rare, except for those located in the oral cavity. The first case of an angioleiomyoma of the digestive system in English literature was documented in 1969 [4] and included a 65-year-old female with a long-standing “blister” 5 mm in size in the hard palate. At that time, angioleiomyomas were referred to as vascular leiomyomas or angiomyomas because they were considered part of the leiomyoma spectrum. Regarding the gastrointestinal tract, the first documented case of angioleiomyoma was reported by Gadaleanu and Popescu in 1988 and involved the duodenojejunal flexure of a 31-year-old female patient [5]. In 1969, Enziger et al. classified leiomyomas into three major groups based on histological features: vascular, solid, and epithelioid [6]. In 1973, Morimoto et al. subclassified vascular leiomyomas into solid, cavernous, and venous type [6].

In the present study, English literature from 1969 to present was searched using the terms “angioleiomyoma” and “vascular leiomyoma” in the PubMed database to identify the clinicopathological features of this entity in the digestive system. A total of 13 cases (present case included) were identified regarding the gastrointestinal canal and the main features are summarized in Table 1 [5-16].

Angioleiomyomas have been reported to affect any part of the digestive system except the esophagus, gallbladder, and pancreas. Significant sex predilection regarding these lesions does not apparently exist, which contradicts the established predominance of soft tissue angioleiomyomas in females [1,2]. Angioleiomyomas can occur at any age; the youngest patient was 21 years of age and presented with a jejunal lesion [6] and the oldest was 71 years of age with an anal lesion [14]. A clear correlation between tumor size and location in the gastrointestinal tract is not apparent.

In the present case, the patient presented with no relevant symptoms; however, angioleiomyomas of the gastrointestinal tract most often exhibit diverse symptomatology based on the size and location of the lesion. The symptoms are most frequently a result of gastrointestinal tract obstruction and disruption of its normal architecture and include hemorrhage, diarrhea, and lump/pressure sensation. In a more recent study, perforation of the ileum due to an angioleiomyoma was reported [15].

Several imaging modalities, including endoscopy, ultrasound, MRI, CT, and angiography were utilized to characterize the lesion. Ultrasound revealed a hypoechoic mass with internal vascularity and CT showed a soft tissue density mass. MRI is the modality used to identify the most helpful features in terms of differential diagnosis. Angioleiomyomas are typically T1 isointense and T2 hyperintense enhancing masses that may have a dark reticular sign and/or hypointense peripheral rim. The dark reticular sign on T2-weighted MRI has been described a characteristic feature of angioleiomyoma, usually of the cavernous and venous type [17-19]. However, the resemblance of angioleiomyoma imaging features to those of other entities renders preoperative diagnosis solely based on imaging studies highly challenging, especially when regarding digestive angioleiomyomas, which are relatively uncommon [17,18].

The clinical differential diagnosis includes more commonly occurring tumors, such as GISTs or other more aggressive malignancies [15]. Although angioleiomyomas, myopericytomas, and leiomyomas share overlapping characteristics, angioleiomyomas are distinguished based on a prominent vascular component, with smooth muscle fibers radiating from vascular channels. This contrasts with the typical concentric perivascular arrangement of myopericytomas and the well-organized fascicular architecture of leiomyomas, which lack significant vascular proliferation. Notably, angioleiomyomas may also exhibit variable amounts of adipose tissue [1,2].

Differential diagnosis of angiomyolipoma is challenging for pathologists and has a potential risk of misclassification [20]. Cases of angiomyolipoma displaying the classic triphasic histology (i.e., blood vessels, smooth muscle, and adipose tissue) accompanied by an absence of melanocytic marker expression have been described in both renal and extra-renal sites [21-24]. Conversely, in several papers, the diagnosis of angiomyolipoma was clearly disregarded when melanocytic markers were negative because a perivascular epithelioid cell origin cannot be supported [25-27]. In those cases, the authors proposed the terms angioleiomyoma with fat or angiolipoleiomyoma. To improve the accuracy of the diagnosis, a broader immunohistochemical panel can be utilized, including microphthalmia transcription factor, cathepsin K, or TFE3 to support the PEComatous origin [28]. Furthermore, electron microscopy could be used for visualizing premelanosome-like granules as documented in prior studies of renal amelanotic angiomyolipomas [21]. However, the most important aspect for the diagnosis remains the morphological distinction between these entities. Specifically, in angiomyolipoma, the smooth muscle component usually displays a characteristic pale/clear and/or granular cytoplasm that is typical of PEComas and has a more mature appearance with the formation of distinct fascicles. Although rarely, angioleiomyomas may contain fat, possibly entrapped during perivascular smooth muscle proliferation corresponding to submucosal adipose tissue, as in the present case. Conversely, the hypothesis of angioleiomyomas with adipocytic metaplasia is worth consideration [2,25].

The subclassification proposed by Morimoto et al. has been seldom reported, possibly due to its limited clinical significance [6]. In the few cases when mentioned, the cavernous subtype was the most prevalent.

Treatment options exclusively encompass either excision of the tumor or partial excision of the affected area of the gastrointestinal tract. Complete excision of angioleiomyomas is considered curative [1,2] and relapse has not been reported in any documented cases.

Although rare, angioleiomyomas can be found in almost any part of the digestive system. The presence of blood vessels, smooth muscle, and adipose tissue may lead to an erroneous diagnosis of angiomyolipoma. Ancillary studies can be helpful but should be correlated and interpreted with respect to the histomorphologic features. Pathologists, radiologists, and surgeons should be aware of this rare entity and consider it in their differential diagnosis. Although angioleiomyomas of the digestive system are rare, they are clinically significantly relevant due to their potential presentation as more aggressive lesions, which can lead to serious implications for patient management. The nonspecific clinical presentation and overlapping imaging characteristics of angioleiomyomas are challenging for an accurate preoperative diagnosis. Therefore, reliable histopathological identification based on characteristic morphological and immunohistochemical features, is crucial to avoid misclassification. Future research should explore the molecular and immunohistochemical profiles of angioleiomyomas in the digestive system, their actual incidence in the population, and the prognostic and diagnostic significance of the different histopathological subtypes.

Notes

Ethics Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the patient. Institutional Review Board approval was waived due to the use of retrospective, de-identified data.

Availability of Data and Material

All data generated or analyzed during the study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files).

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: GK, TK. Data curation: GK, CT, TG, CH. Formal analysis: GK, CT, TK. Investigation: GK, CT. Methodology: GK, CT, TK. Project administration: TK. Supervision: TK. Writing—original draft: GK, CT, TK. Writing—review & editing: GK, CT, TG, CC, KS, TK. Approval of final manuscript: all authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no potential conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

No funding to declare.