Establishing molecular pathology curriculum for pathology trainees and continued medical education: a collaborative work from the Molecular Pathology Study Group of the Korean Society of Pathologists

Article information

Abstract

Background

The importance of molecular pathology tests has increased during the last decade, and there is a great need for efficient training of molecular pathology for pathology trainees and as continued medical education.

Methods

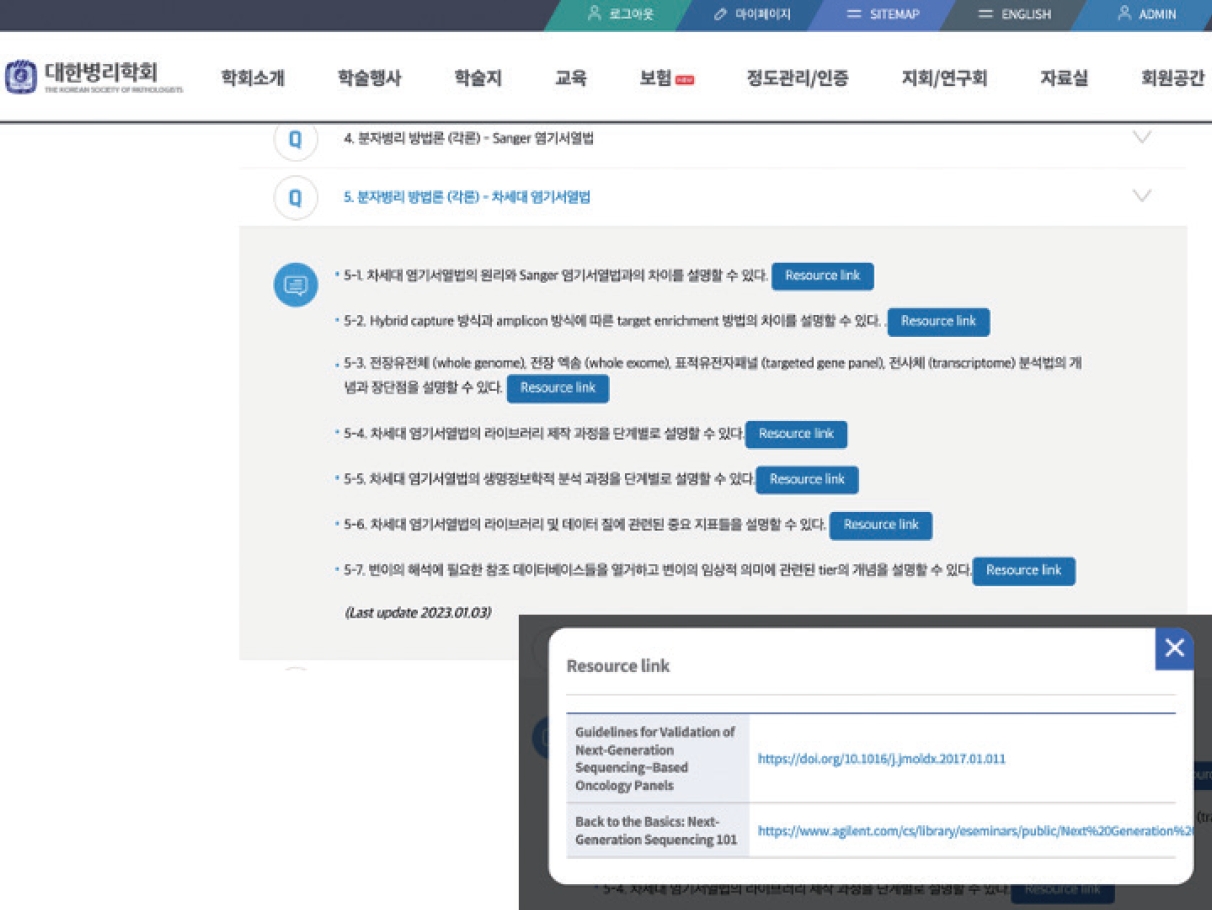

The Molecular Pathology Study Group of the Korean Society of Pathologists appointed a task force composed of experienced molecular pathologists to develop a refined educational curriculum of molecular pathology. A 3-day online educational session was held based on the newly established structure of learning objectives; the audience were asked to score their understanding of 22 selected learning objectives before and after the session to assess the effect of structured education.

Results

The structured objectives and goals of molecular pathology was established and posted as a web-based interface which can serve as a knowledge bank of molecular pathology. A total of 201 pathologists participated in the educational session. For all 22 learning objectives, the scores of self-reported understanding increased after educational session by 9.9 points on average (range, 6.6 to 17.0). The most effectively improved items were objectives from next-generation sequencing (NGS) section: ‘NGS library preparation and quality control’ (score increased from 51.8 to 68.8), ‘NGS interpretation of variants and reference database’ (score increased from 54.1 to 68.0), and ‘whole genome, whole exome, and targeted gene sequencing’ (score increased from 58.2 to 71.2). Qualitative responses regarding the adequacy of refined educational curriculum were collected, where favorable comments dominated.

Conclusions

Approach toward the education of molecular pathology was refined, which would greatly benefit the future trainees.

Molecular pathology (MP) refers to various diagnostic techniques based on the handling of nucleic acids [1]. The area of MP has been increasing in both its amount and importance since the introduction of targeted therapy and integrated molecular pathologic diagnosis [2-4]. Especially after the introduction of clinical next-generation sequencing (NGS), the importance of MP for practicing pathologists is continuously growing [5]. In South Korea, the clinical NGS has become a part of daily practice since 2017, and the test volumes have increased, and currently in the year 2023, a total of 69 institutions in Korea is performing clinical NGS tests [6]. In the year 2021, 15,842 NGS tests were performed nationwide according to the statistics obtained from the Big Data Hub of Korean Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service [6]. Therefore, there is a great need for efficient training of MP for pathology trainees and as continued medical education (CME).

In United States, the Association for Molecular Pathology Training and Education Committee presented general goals and objectives for MP education in residency program in 1999 [7]. In Korea, general goals and objectives for pathology residency training is demonstrated by Ministry of Health and Welfare [8], which includes the statements regarding specialized tests including MP techniques; however, well organized and structured educational curriculum is still insufficient and not well established yet.

Unlike in United States, practicing MP in Korea has some unique features; for instance, (1) departments of clinical pathology and anatomic pathology are separated, (2) MP testings and reimbursements are controlled under unique governmental regulations, and (3) some of the genetic features of Korean population is different from the Western data. Thus, customized MP educational curriculum well suited for the Korean practicing environment should be developed for adequate training of Korean pathology residence and CME.

To develop a refined educational curriculum of MP, the Molecular Pathology Study Group of the Korean Society of Pathologists (KSP) appointed a task force (TF) composed of experienced molecular pathologists, structured objectives and goals of MP and posted as a web-based interface, provided 3-day online structured MP educational session, and received immediate feedbacks from the trainees and practicing pathologists.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The Molecular Pathology Study Group of the KSP appointed a TF composed of experienced molecular pathologists to develop a refined educational curriculum of MP. The TF initially started with literature review of MP education and training approaches in US and established structured key learning objectives of MP training in Korea. Online resource repository composed of key references for each learning objective was organized by the TF.

Based on the newly established structure of learning objectives, 3-day online MP educational sessions were held on February 2, 12, and 26, 2022. To assess the usefulness of the learning objective-oriented educational sessions, the TF also created survey asking the session audience to score their understanding of selected learning objectives before and after the session by Likert scale.

RESULTS

Lessons from US experiences

In US, the need for adequate MP education started around late 1990s [9], owing to the advances in the application of molecular biology technology. In the year 1999, the Training and Education Committee of Association for Molecular Pathology (AMP) provides an outline of important elements of resident MP education [7]. The general goals provided by the AMP include basic knowledge in human genetics, basics of molecular biology, and specific skills relevant to microbiology, molecular oncology, genetics, histocompatibility, and identity determination [7]. In addition, the AMP also provided the list of sentinel papers highlighting the important concepts of infectious disease, molecular oncology, inherited disorders, histocompatibility, and identity determination [7].

Along with the advances in NGS technologies and increase in the importance of genomic medicine in the clinical practice, the need for the refinement of educational topics was increased over time. Therefore, the Stanford group pioneered to establish a genomic pathology curriculum–so-called The Stanford Open Curriculum–to help pathology residents build a foundation for the understanding of genomic medicine and the implications for clinical practice [10]. The 10 lectures encompassed the overview of the fundamental principles of molecular biology, clinical genomics, and personalized medicine, and the curriculum also provided 7 additional topics as the elective course of advanced genomic medicine [11].

However, the real-world data suggested that there existed a significant discrepancy between the literal description of curriculum and the subjective perception among the trainees. In a survey of 42 pathology residency programs, only 31% reported that genomic medicine training was included in their program [12]. The serious educational gap prompted the pathologists and medical education specialists in US to organize Training Residents in Genomics (TRIG) Working Group. The TRIG Working Group conducted a nationwide survey for the in-serviced pathology residents in 2013 [13]. 42% and 7% of residents reported that they had no training of genomic medicine and MP during their residency, respectively [13]. When asked whether they were able to discuss MP or genomic medicine test results with a provider, only 13% and 28% of the responders scored that their ability as “very good/excellent” [13].

On observing the obvious educational gap, the Training and Educational Committee of AMP appointed the Molecular Curriculum Task Force; the TF developed an organized curriculum in MP for residents [14]. The major subjects of curriculum included basic MP goals/laboratory management, basic concepts in molecular biology and genetics, technology, inherited disorders, oncology, infectious diseases, pharmacogenetics, histocompatibility and identity, genomics, and information management [14]. Besides, TRIG Working Group provided online genomic pathology modules to improve genomics knowledge and the ability to utilize online genomics tools (https://www.pathologylearning.org/trig). The first version was introduced in the year 2016, and the most recent updates were added in the year 2020 [15,16]. To date, the TRIG has expanded their work toward the education of the undergraduate medical students [17].

Learning objectives and online repository

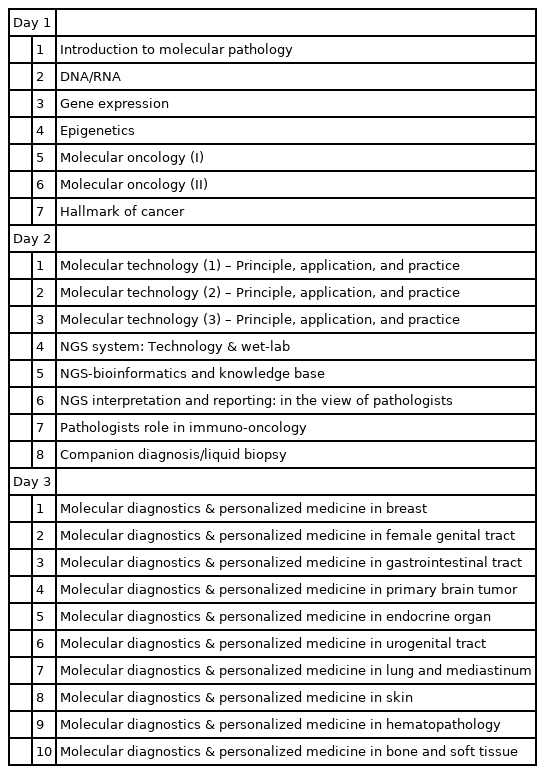

For adaptation of US experiences into real-world education in South Korea, 13 major topics of MP education was selected by the TF, and detailed description of objectives and goals were generated under each topic, comprising a total of 75 structured items as shown in Table 1. The structured objectives included basic items such as ‘1-2. Definition of genome, exome, proteome, transcriptome, and metabolome’, and further encompassed timely topics such as ‘2-10. Able to explain the definitions of companion diagnostics and complementary diagnostics.’

To provide high-quality resources for trainees, TF members were assigned with each major topic and reviewed the relevant online resources and assessed the quality of contents. After the thorough review of contents, the most adequate learning sources were selected and gathered to form the online repository of MP learning objectives. The online repository became available for all the members of KSP via the official webpage (https://www.pathology.or.kr/html/?pmode=boardlist&MMC_pid=306&cate=study) (Fig. 1).

Snapshot showing the online repository of structured molecular pathology goals and learning objectives. The repository of learning objectives became available online for all the members of Korean Society of Pathologists. Each element is linked with high-quality learning resources as shown in the bottom right panel.

3-Day online structured educational session and survey

Based on the structural objectives, the Molecular Pathology Study Group of the KSP planned and held 3-day online structured educational session in February 2022 (Table 2). A total of 201 pathologists participated in the educational session.

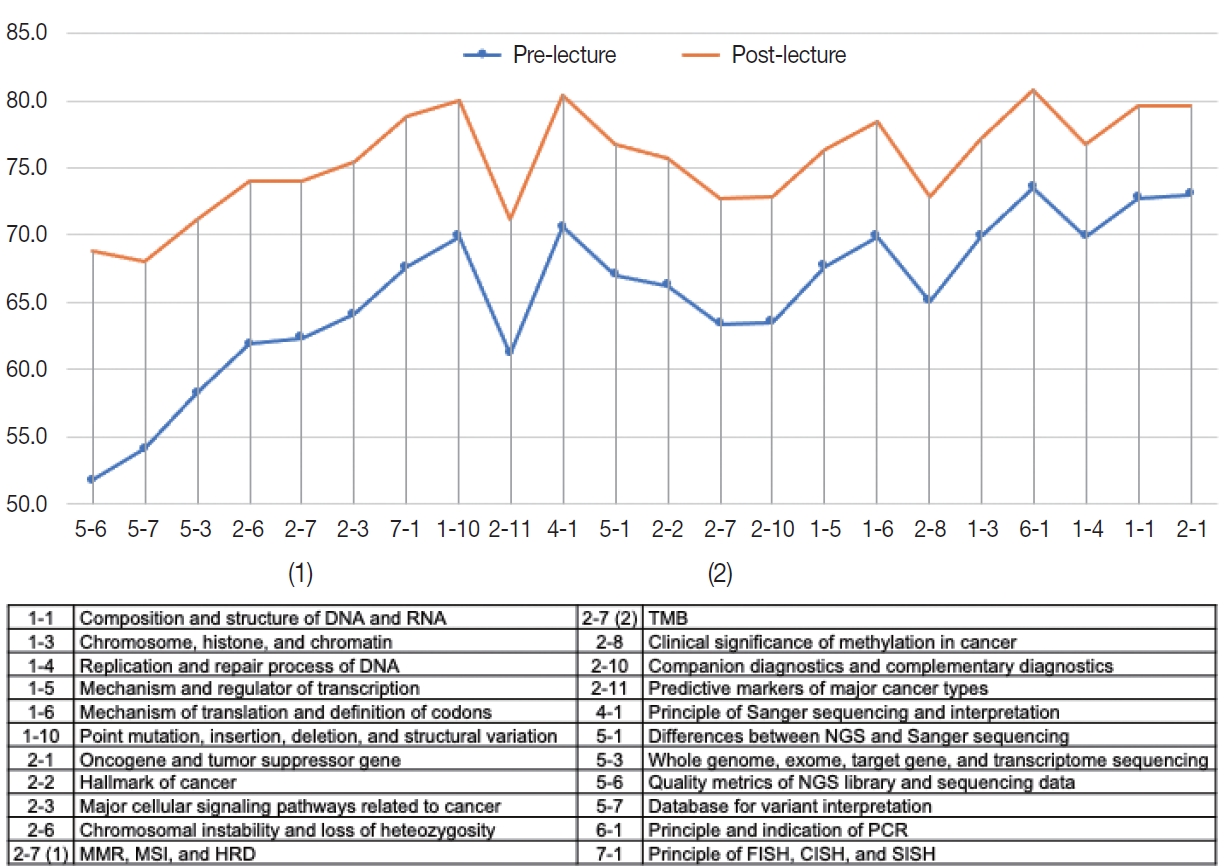

To immediately assess the effectiveness of refined educational session, the TF selected 22 key learning objectives out of total 75 elements and asked the session audience to grade their understanding of each topic before and after the lecture, respectively. The survey was performed at day 1 and day 2 with response rates as follows: day 1 pre-lecture, 93/201 (46.3%); day 1 post-lecture 83/201 (41.3%); day 2 pre-lecture 50/201 (24.9%); day 2 post-lecture 34/201 (16.9%).

Among 22 learning objectives (Fig. 2), the audience reported higher scores regarding their prior understanding on the basic concepts of MP including ‘1-1. Composition and structure of DNA and RNA’ (mean score 72.8), ‘2-1. Oncogene and tumor suppressor gene’ (mean score 73.0), and ‘6-1. Principle and indication of PCR’ (mean score 73.5). In contrast, self-reported understanding prior to the session was lowest in the topics related to NGS: ‘5-6. Quality metrics of NGS library and sequencing data’ (mean score 51.8); ‘5-7. Database for variant interpretation’ (mean score 54.1); ‘5-3. Whole genome, whole exome, target gene, and transcriptome sequencing’ (mean score 58.2).

Comparison of subjective understandings on the selected topics between before and after the 3-day structured course. The participants of 3-day structured course were asked to grade their subjective understanding before and after the lecture, and the results for selected topics are depicted.

The scores of self-reported understandings increased after educational session by 9.9 points on average (range, 6.6 to 17.0) (Fig. 2). Of interest, the most effectively improved items were those with lowest pre-lecture scores as follows: ‘5-6. Quality metrics of NGS library and sequencing data’ (score increased from 51.8 to 68.8); ‘5-7. Database for variant interpretation’ (score increased from 54.1 to 68.0); ‘5-3. Whole genome, whole exome, target gene, and transcriptome sequencing’ (score increased from 58.2 to 71.2).

Additionally qualitative responses regarding the adequacy of refined educational curriculum were collected, where favorable comments dominated. The audience provided responses regarding the further suggestions regarding the topic for future educational sessions, and some of the examples are as follows: real-world clinical NGS cases, NGS raw data analysis using R software, wet-lab techniques of NGS, and cutting-edge novel technologies including proteomics and proteogenomics.

DISCUSSION

In line with the recent increase in need for the high-quality education of MP for pathology trainees, the Molecular Pathology Study Group of the KSP initiated this project for the development of MP curriculum.

The project first started with the review of US experiences on the MP education during the last decade [7,9-12,14-18]. Next, the project focused on the establishment of the structured objectives and goals of MP, which was later online resource repository within KSP official website to enable continuous update and better accessibility. Also, 3-day structured course was held according to the newly established learning objectives, which received favorable responses from the audience.

The TF appointed by the Molecular Pathology Study Group of the KSP specifically aimed to list up learning objectives and goals, which can readily be introduced into practical educational sessions, like the successful experience by TRIG Working Group [12,16,17]. These efforts resulted in the production of online resource repository and 3-day online MP course. The favorable responses from the KSP members suggest that the purpose of this project was relatively well achieved. Still, we noticed some limitations and further challenges.

First, unlike the survey performed by TRIG [13], the overall response rate of the survey was low, which implies that the data may not represent the opinions of all the pathology residents in Korea. In addition, our survey did not collect the information with respect to the training levels of audience; since the subjective need for certain items among the learning objectives may differ according to the training level or current job description, further collection of feedbacks from variable groups among KSP members should follow. Moreover, besides the subjective assessment of participants’ understandings, well-prepared questionnaires and self-assessment programs for objective measurement of participants’ academic accomplishment should be provided in the near future.

The most important challenge that need to be addressed would be the sustainability and timely adaptability of the education curriculum. The area of MP and genomic medicine is one of the most rapidly evolving sectors among the field of pathology [3,4,19]. The efforts from small group of eager pathologists would not be able to maintain the long-lasting high-quality educational platform. Continuous feedback from all the KSP members along with the leadership from Molecular Pathology Study Group of KSP could surely make the quality of MP education better, which would benefit the whole medical society in South Korea. In addition, an in-depth pool of high-quality assessment contents should be further developed for proper evaluation of the educational effect of this novel approach.

In conclusion, for better education of MP within KSP, structured learning objectives and goals of MP was refined and listed, which resulted in the production of online reference repository and 3-day MP lecture course. Approach toward the education of MP was refined, and this big step can further greatly benefit the future trainees.

Notes

Ethics Statement

Not applicable.

Availability of Data and Material

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: AL. Data curation: JK (Jiwon Koh), HYP, UC, JKW, AL. Formal analysis: JK (Jiwon Koh). Funding acquisition: AL. Investigation: JK (Jiwon Koh), HYP, JKW, AL. Methodology: JK (Jiwon Koh), JKW, AL. Resources: JK (Jiwon Koh), HYP, JMB, JK (Jun Kang), UC, SEL, HK, MEH, JKW, YLC, WSK, AL. Writing—original draft: JK (Jiwon Koh). Writing—review & editing: all authors. Approval of final manuscript: all authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no potential conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

This research was supported by The Korean Society of Pathologists Grant No. KSPG2021-02.